Apart from the odd lyric, no writing about music here. This is a recent book chapter, the content of which seems appropriate for the new year. Back to music writing next week.

Don't let me hear you say life's taking you nowhere, angel.

Look at that sky, life's begun

Nights are warm and the days are young

David Bowie, Golden Years

Those of us entering retirement now were born in the golden years, inspired by their values and ideals, and bringing what we learned then and through subsequent experiences to our own golden years. The years ahead give us opportunities to apply our optimism and knowledge to new challenges.

This perspective fueled the idea of reuniting with our peers from fifty years ago, who were part of a unique and somewhat unconventional degree programme at Middlesex Polytechnic - the BSc in Society & Technology, known as Soc & Tech. The course was a pioneering venture in interdisciplinary education.

In an effort to rekindle connections and share experiences, we invited fellow alumni and as many former staff members as we could track down to contribute to a commemorative book. Each participant was given up to 1,000 words to reflect on why they joined Soc & Tech, their most memorable moments, and the course's impact on their subsequent life journey. This project was more than a trip down memory lane; it was a step towards understanding how these reconnections could empower us to approach the coming years with positivity and creativity.

An open door

What stands out from our project is how the course, and the Polytechnic system in general, offered an open door to people from a whole variety of backgrounds to rush through and benefit from higher education.

Many of us entered the course from environments characterised by a culture of failure. One individual recalled attending a primary school where "everyone had failed their 11+", a scenario far from unique. Another spoke of their time in a Secondary Modern school where "nothing was expected of you, so I did very little." Prior to the course, several described their lives in terms of low expectations, dead-end jobs, failed exams, and a general sense of being written off.

In stark contrast, Soc & Tech represented a nurturing and nonjudgmental space: "I never felt judged; I always remember it as such a constructive and supportive experience." The experience was all-encompassing: "It felt like one long discussion, where the lines between class, coffee break, and socializing blurred. It was a continuous, vibrant conversation, debate, and argument about the most pressing issues of the day." And it was transformative: "My classmates shifted my worldview from being a factory worker to something entirely different."

Through that open door streamed factory apprentices, office workers, lorry drivers, electricians, and individuals who had struggled academically at school or had been let down by other courses. On the other side of that door, they discovered a world rich with collaboration, enlightenment, activism, and ideas, leading them to futures they could not have imagined before.

History makers

It has been said that people make their own history—they explore and define alternative futures based on their hopes and aspirations. These futures are also shaped by the ideas and inspiration transmitted from the past. We build on the history of others to create a new future for ourselves. That is much how our course worked. We each used the course as a starting point - bending it, adapting it, and subverting it. A vital part of that subversion was influenced by other factors from the wider world at that time.

My argument here is that the creation of our course - and our engagement with it - coincided with a unique historical moment when alternative futures became vivid and viable. We were at the moment of peak optimism, providing a positive spirit of experimentation that influenced our actions, thoughts, and aspirations.

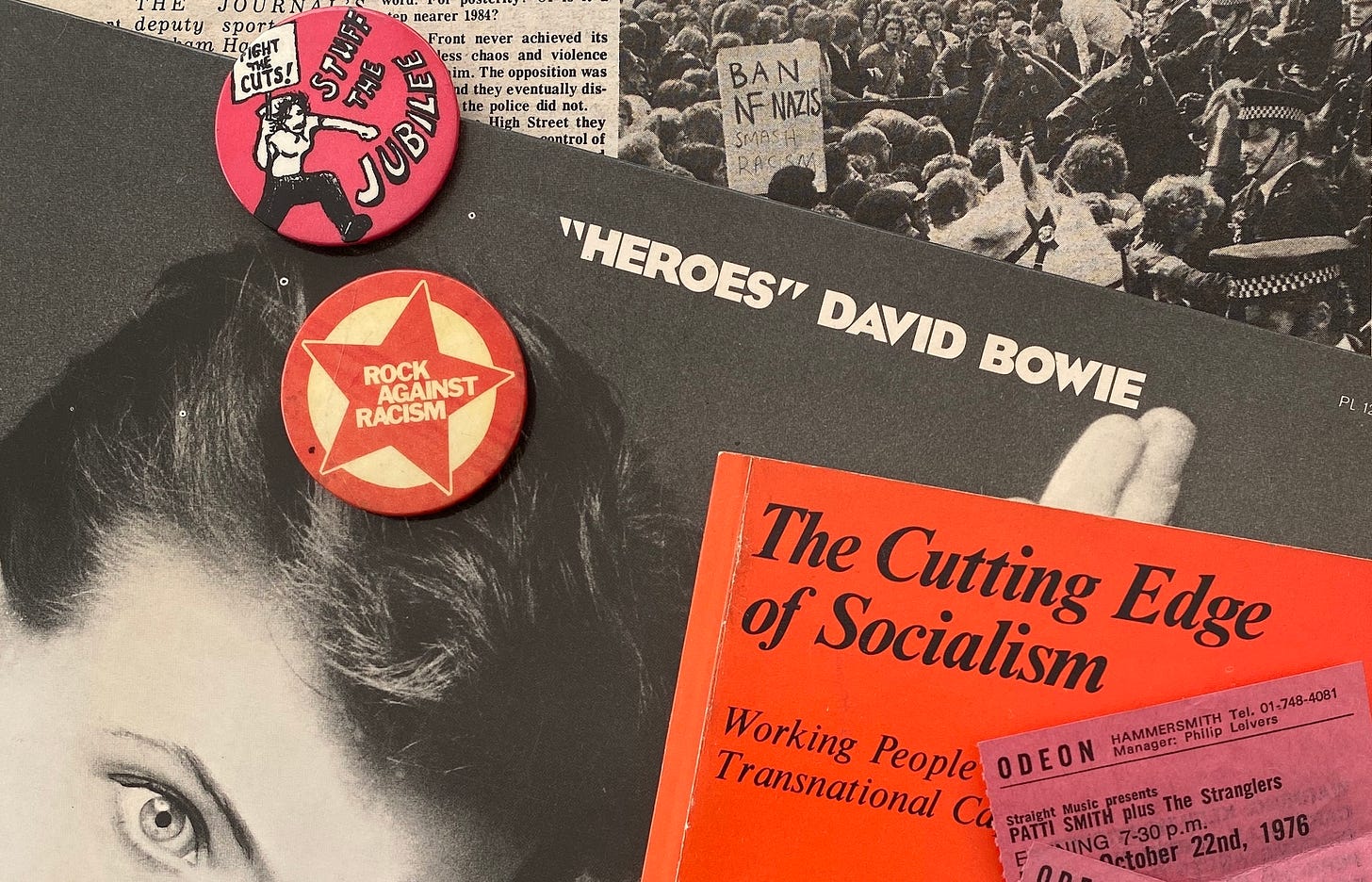

In the early 1970s a series of significant developments unfolded, each contributing to the alternative and critical discourses around society and technology. These events, marked by the convergence of societal shifts and technological advances, reflected a period of exploration, dissent, and the questioning of established norms. They took place at the very end of what historian Eric Hobsbawm describes as his golden years - the 1945-75 period when it was believed that ways had been found (or could be found) to solve (or minimise) the economic, social and political problems of capitalism - or design viable alternatives to it.

To use Hobsbawm’s term, the period after 1975 was the landslide where - to put it crudely - all political optimism slid out of view (unless you lived in East Asia). But ours was an education and inspiration rooted in the peak optimism moment of those golden years, and we are joined to it by a golden thread of constructive discontent that could serve us well today. Back then, all the news aligned - new left, new age and new technology all jostled with each other for attention and commitment from a new generation - and in us they fused together.

The news agents

Between 1970 and 1973, three magazines were launched that reflected this new thinking for new times and - above all - positive and practical strategies for change. From 1973 Spare Rib provided a focus for feminist debate and discussion around collective strategies for change. If we’re looking for a fundamental shift in the tectonic plates of ‘the left’ in the post war period, then Spare Rib - and the movement it was part of and gave a focus to - is it.

Also launched in 1973, Undercurrents billed itself as “the magazine of alternative science and technology”, reflecting the growing interest in both alternative technologies and the politics of science. Finally we had from 1970 The Ecologist and the 1972 book which spun out of the magazine - Blueprint for Survival - which made the case for small, decentralised communities and human-centred technological systems. Alongside these magazines in the early 1970s were countless books that were part of this new thinking around peak optimism. Three other initiatives were also crucial.

Opened in the autumn of 1973, the Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT), was a beacon of innovation nestled in a disused slate quarry near Machynlleth, North Wales. It probably didn’t seem like much of a beacon of anything at the time, but its beacon-status is established by it being - 50 years on - still there. As the doors of CAT swung open, it symbolised a departure from the conventional trajectory of technological progress. Here, a community of thinkers and pioneers sought alternative paths, exploring sustainable and eco-friendly technologies. The ethos of CAT emphasised the need for a more harmonious relationship between technology and the environment.

Just months before CAT opened, across the Atlantic at Xerox PARC in California, the landscape of computing was undergoing a paradigm shift. The development of the first computer with a ‘desktop’ Graphical User Interface (GUI) plus mouse marked a departure from the command-line interfaces that had dominated computers. This innovation foreshadowed a more user-friendly and visually intuitive approach to technology. It took a few years and the enterprise of Wozniak and Jobs to show just how revolutionary this approach could be, and I type these words on the latest descendent of their invention: my Mac. Mind you, while mice and icons were the thing in Palo Alto, at Middlesex Poly we still used punch cards.

In November 1974 a different yet related narrative was unfolding within an office at Whitehall’s Department of Industry. At a meeting with members of the Lucas Aerospace Joint Shop Stewards Combine Committee who were facing massive job losses, Tony Benn suggested that they embark on a unique venture—a workers' plan for the company. This proposal sought to empower the workforce to actively shape the technological direction of the company. The workers' plan at Lucas Aerospace exemplified an alternative discourse that challenged the traditional hierarchies and decision-making structures within industrial settings and - significantly - proposed the idea of socially useful production.

So there we have it.

Within that very period our course was just getting off the ground, we had new, bold and above all constructive ideas you could purchase at your local newsagent. For a modest 30p you could buy a future based on fraternity not patriarchy. Alongside this we were shown working prototypes of alternative technological futures. We had a future based on sustainable energy, agriculture and living systems. We had a future based on human-centred digital technology and computing for the people. And we had a future where the inherent creativity and inventiveness of working people could design the systems and products of industry along socially useful lines. Arcadia was already being built. And we would build a part of it in North London.

Constructive discontent

If we couldn’t build it - we’d squat it.

In London during the 1970s, an estimated 20–30,000 people were squatting in empty dwellings. This was a response to the actions of speculative landlords, developers and local councils who in some cases were leaving whole streets of houses empty, earmarked for demolition. The squatting movement provided physical spaces for experiments in collective living and community activism to develop. Squats didn’t just provide affordable housing, but places that provided women’s centres, refuges, bookshops, food shops and art centres. They also created spaces where feminist and LGBT communities could flourish. In London’s East End, Bengali families suffering violent racist attacks and denied decent housing occupied empty properties around Whitechapel. Their use of squatting as direct political action led to the GLC providing tenancies in safe neighbourhoods.

Soc & Tech students were active participants in all of this. The built environment was a technology that could be reinvented, redesigned and repurposed to address alternative social objectives. Margaret Gibson and Nik Nikloff were two of those who launched the Habbarfield Housing Cooperative, which negotiated with local authorities in North London to provide short term housing - a form of ‘licenced squatting’. From Walthamstow to Barnet, the cooperative secured homes for hundreds of individuals, in what was a practical and political response to London’s housing crisis. Some of the houses even had inside toilets, although one house I lived in didn’t have any toilet at all. Then there was the enormous house that was well blessed with inside toilets, but somewhat wanting in terms of bedrooms. It was there, in a novel twist on the en suite concept, that I ended up living in a toilet for a few months in 1978.

Soc & Tech was an education of constructive discontent. God knows we had enough to be angry about, and not just the shortage of affordable housing (not to mention living in a toilet). But we converted the negativity of anger into a positive, constructive and creative energy - and we carried on using that energy in the lives that we each went on to make. We were (and still are) constructivists - in the sense not only that we apply a practical, positive approach, but in the more theoretical sense that we are adept at constructing new understandings and knowledge through experience and social discourse, integrating prior knowledge with with new information about the challenges and opportunities we encounter.

The course’s success (and perhaps a reason for its eventual demise) was its flowering at that very moment of peak optimism in our political culture. We all benefited from that - from the opportunities and ideals of the polytechnic system, the vision of those who created our education and - of course - from being with each other as each individual responded in their own way to the new ideas and possibilities of that time. It was an ideal, perhaps unique time to be a constructive discontent.

Optimism gives us agency

Our project of reflection and re-connection holds immense value—not only as a way to evaluate where we are and the paths we’ve traveled but also as a potential spark for new collaborations and shared inspiration. While the future outcomes of this work remain uncertain, one thing is clear: it serves as a powerful reminder of a vital lesson for our future endeavours.

I’m with Angela Davis on this. She underlines the necessity of optimism, echoing Gramsci's sentiment: "I don't think we have any alternative other than remaining optimistic. Optimism is an absolute necessity, even if it's only optimism of the will and pessimism of the intellect.”

This perspective is not just philosophical rhetoric. It is grounded in evidence—recent research highlights the tangible impact optimism has on the health of older adults. Studies consistently show that optimism correlates with better physical health, a lower incidence of chronic illnesses, and greater resilience in navigating the complexities of aging. Older individuals who cultivate optimism are more likely to embrace healthier lifestyles and exhibit stronger adaptability as they age.

Optimism transcends mere emotion; it is a lens through which we view the world. Recognising this does not dismiss the gravity of the challenges we face—whether it’s war, poverty, or the climate crisis. Instead, optimism becomes essential precisely because it fuels hope and resilience. It drives us to action and strengthens our belief that positive outcomes are possible, even in the face of adversity. It is a catalyst for innovation, inspiring problem-solving and perseverance. Just as importantly, it sustains our mental well-being, which is critical for the long-term effort required to address complex global issues.

Optimism also has a profound social dimension. It fosters collaboration, builds trust, and cultivates environments where ideas and support thrive. Importantly, optimism isn’t about ignoring challenges; it’s about believing in our shared ability to overcome them. This truth is exemplified by our former tutor turned climate activist, Dick Warn, whose work with Extinction Rebellion demonstrates how optimism empowers agency. Optimism, therefore, is not mere wishful thinking; it's a catalyst for action.

Our intellectual and political identities were shaped in an era of unprecedented optimism. While we’ve faced setbacks, disappointments, and failures in building the futures we once envisioned, the only viable way forward remains one of unwavering optimism. This enduring optimism is not just a safeguard during times of personal health challenges; it is also a guiding force as we transition from work-centric lives to redefining our purpose and responsibilities within families and communities. It bolsters our determination to believe in the possibility of a different, better future. The potential for change was real then, and it remains just as potent today.

Optimism also keeps us focused on the future, steering us away from the pitfalls of nostalgia. Nostalgia tends to idealise the past, often dismissing progress in favour of what we’ve lost. In a world that grows more complex by the day, nostalgia’s inclination toward simplicity is unhelpful. There’s a critical distinction between reflecting on our personal histories to understand them and retreating into the half-remembered comforts of the past. It’s a slippery slope between wishing they’d bring back Spangles to voting for Nigel Farage.

Our journey of reflection and re-connection is not merely a pause for introspection. It is an active engagement with the lessons of the past to forge a hopeful and optimistic path forward. This optimism is essential—not only for navigating the challenges of personal health and societal responsibilities but also for confronting global crises. Optimism is a powerful tool that enhances individual well-being while shaping a brighter collective future. By embracing a deeply optimistic outlook, we arm ourselves with the resilience, creativity, and determination needed to overcome life’s challenges and seek new possibilities.

The optimism that once ignited our intellectual and political awakening endures. It drives our belief that a different, better future is still within reach. Let’s continue searching for it.

Once there were mountains on mountains

And once there were sunbirds to soar with

And once I could never be down

Got to keep searching and searching

David Bowie, Station to Station

Author’s note

This is an edited version of a chapter written for the Pictures & Conversations edition of Look Back in Candour. The previous edition of the book is available on Amazon.

The final section above—Optimism Gives Us Agency—is frustratingly brief in its argument. Given the scope of the book this chapter belongs to, the emphasis had to remain on the collective experiences of those involved and the lessons these could offer for the future. As a result, the actual case for optimism could only be touched upon. I am eager to expand on this argument and move beyond the misconception that optimism is merely wishful thinking.

Optimism isn’t about assuming everything will turn out well. Rather, it is a mindset—a belief that, despite the inevitable challenges, we will make progress. Where pessimism fixates on problems, optimism focuses on solutions. In this sense, I would argue that an optimistic mindset is inherently more rigorous. It demands the discipline to confront obstacles honestly while maintaining a clear vision of better outcomes and a willingness to work toward them.

I’m particularly interested in developing a collaborative writing project on the subject of optimism. If this idea resonates with you, let me know—I’d love to explore it further. But why is optimism so important? Quite simply, because it sustains our belief in the future. As President Barack Obama said in 2017:

"If you had to choose any moment in history in which to be born, and you didn’t know in advance whether you were going to be male or female, what country you were going to be from, what your status was… you’d choose right now."

Thanks Mike - I like it - but then I was part of it.

Best Wishes for your Optimism Project.

Ray Massey.

BSc Society & Technology 1975-1979.

A great piece to mull over as we head into 2025. I loved a spangle. I’m fascinated by CAT and a lover of Bowie. Here’s to optimism and hope. Happy New Year.