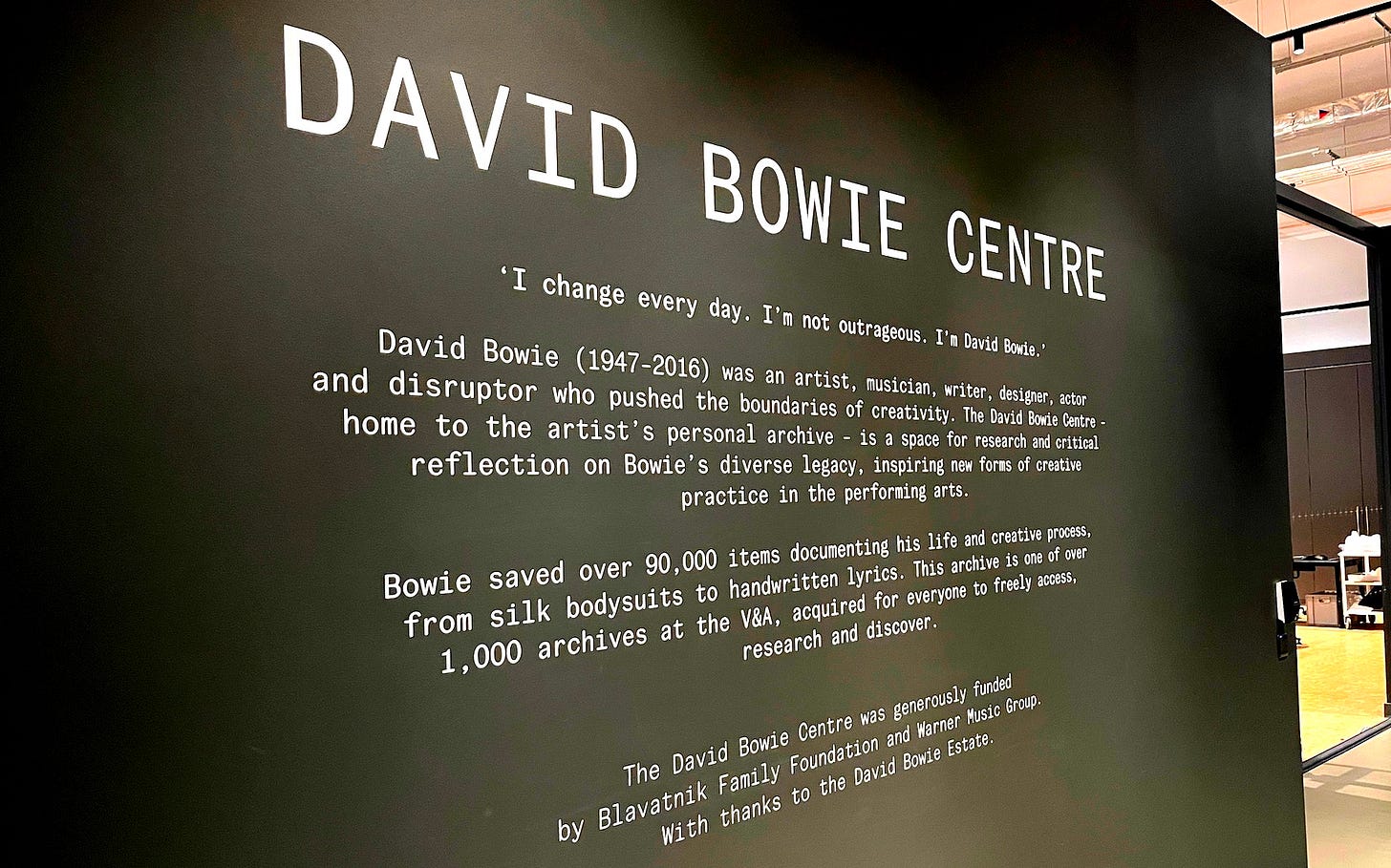

On 9 October the two of us visited The David Bowie Centre, recently opened as part of the V&A East Storehouse in Stratford’s Here East complex — a major new public museum and archive dedicated to making the inner workings of the V&A visible. The Centre houses the artist’s entire personal archive, comprising more than 90,000 items spanning his six-decade career.

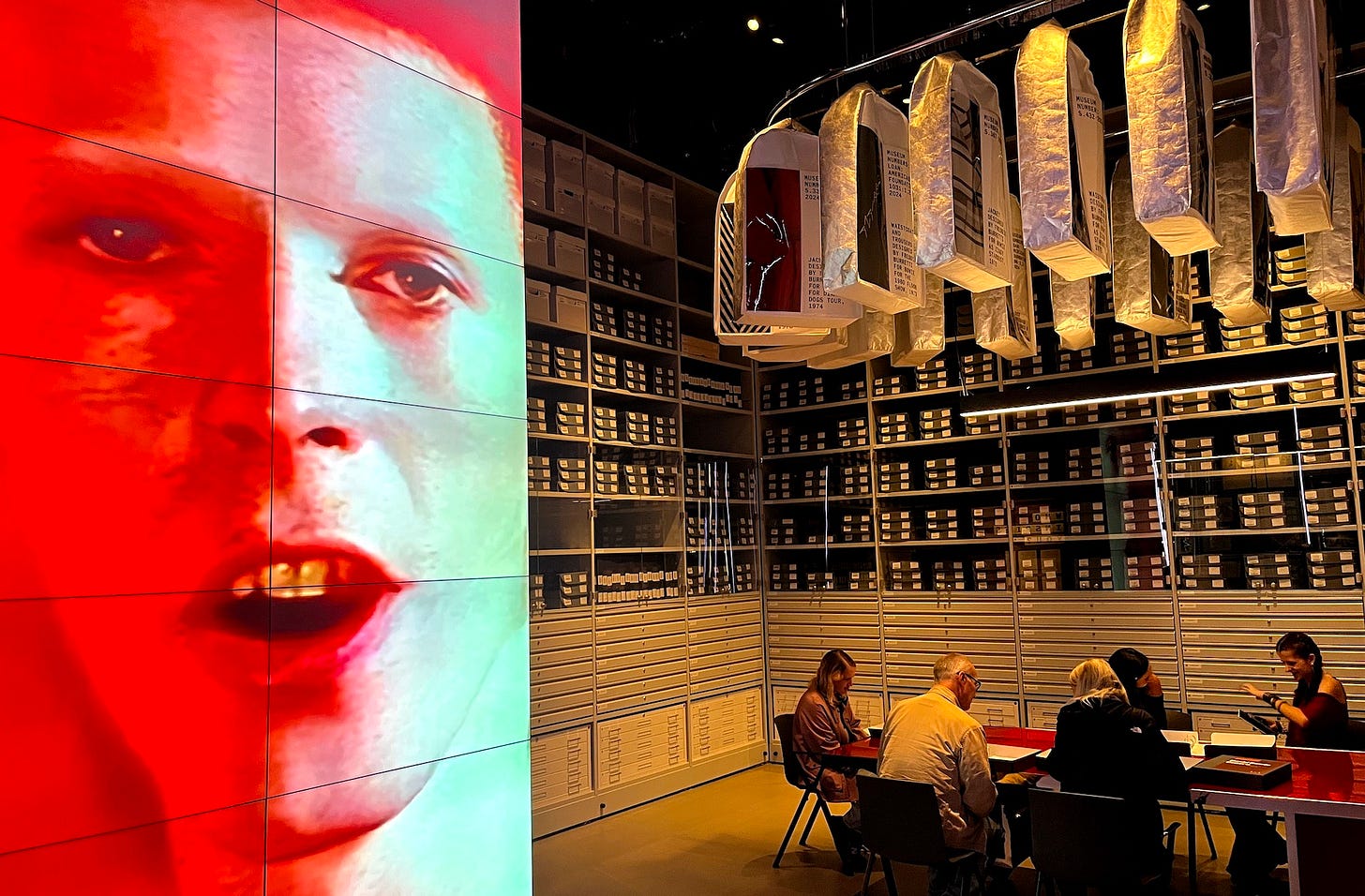

This is not a conventional museum gallery. The Storehouse’s open architecture — with glass walkways, visible storage systems, and on-view conservation labs — redefines the act of archiving as something active and transparent. Within that setting, the Bowie collection becomes both a research resource and a reflection on the creative process itself.

A Living Archive

The V&A acquired the Bowie archive in 2023, seven years after the artist’s death, following the success of its 2013 exhibition David Bowie Is. The new Centre is the first permanent home for the collection, funded by the Blavatnik Family Foundation and Warner Music Group.

Its holdings cover nearly every aspect of Bowie’s work — from notebooks and lyric drafts to stage costumes, set designs, instruments, correspondence, and visual art. It also includes photography, film, and extensive material from Bowie’s collaborations with designers, musicians, and filmmakers.

The collection’s scale is unprecedented: a complete creative life preserved almost in real time.

Handwritten Worlds

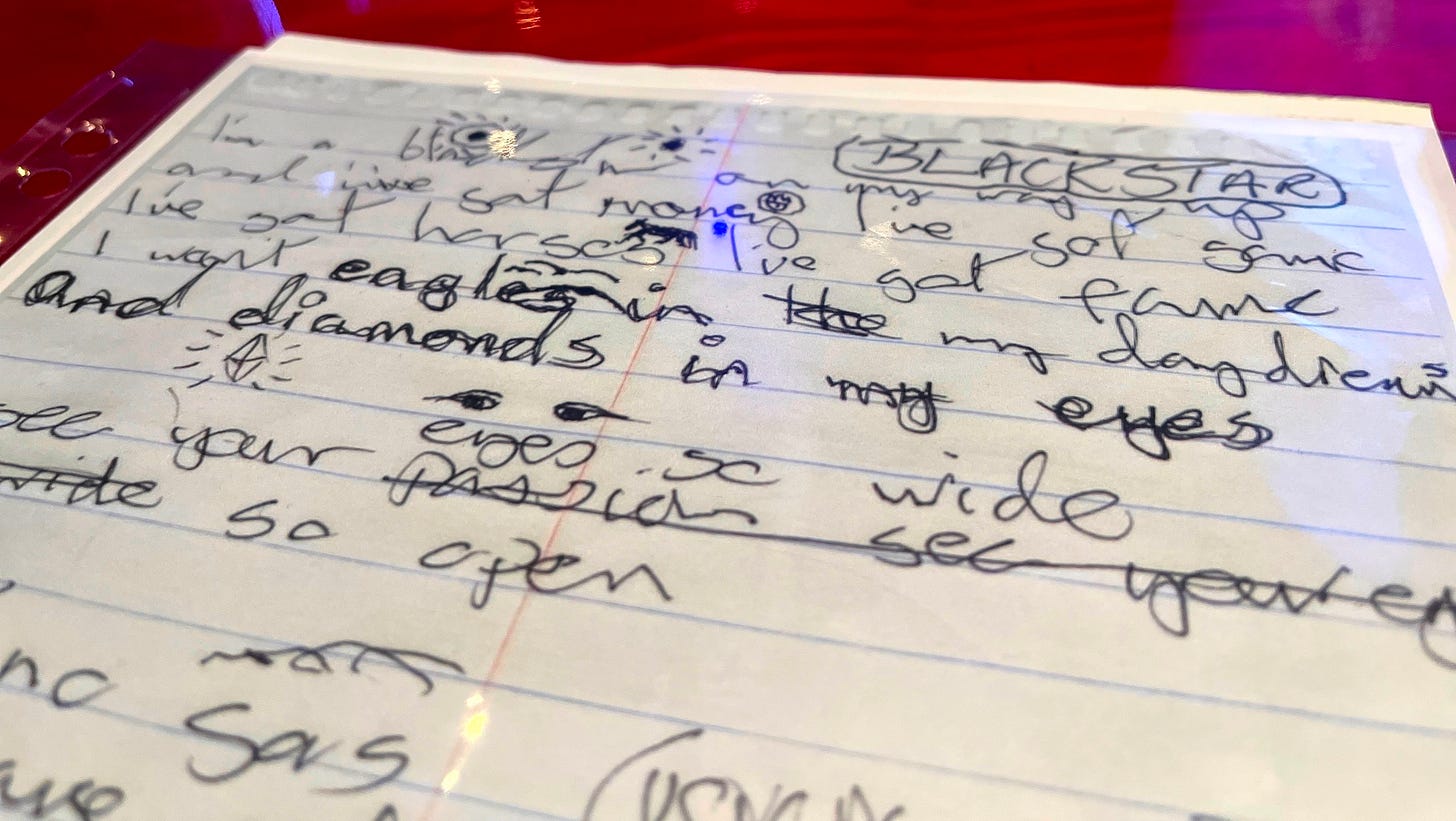

Several lyric manuscripts are on view, tracing Bowie’s approach to writing and editing. A page titled Blackstar, full of quick sketches of stars, eyes, and diamonds, illustrates his habit of embedding imagery into text. The handwriting is restless, the tone experimental.

Also on show are early drafts for 1984 (intended for an unrealized stage musical) revealing Bowie’s long-standing interest in dystopian narratives and theatrical form. Typed and handwritten passages describe a world of “tumbledown buildings” and “Big Brother watching you.”

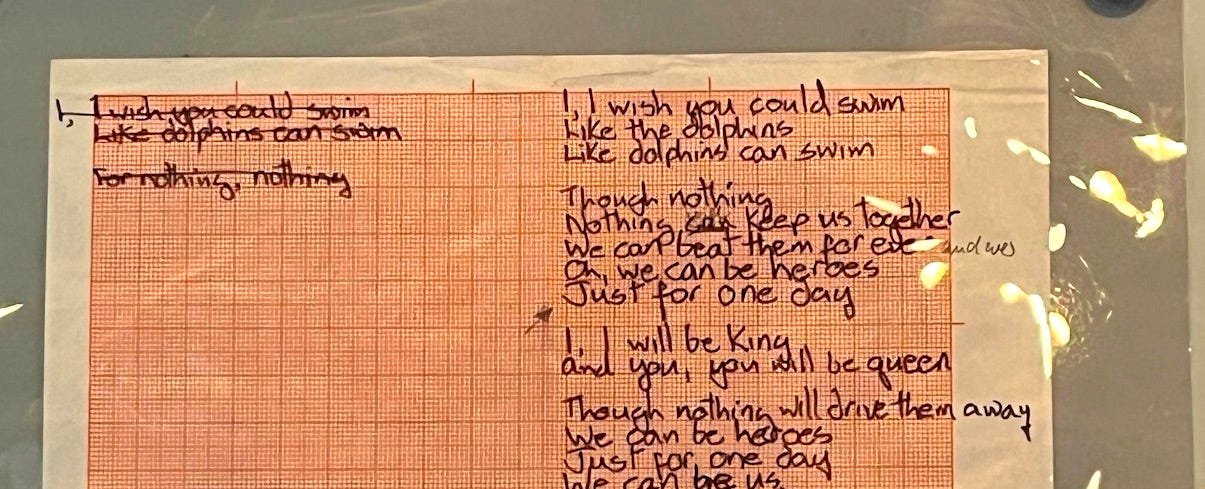

His Berlin-era notes for Heroes show how he refined language for sound rhythm and meaning. The version on display — written on red graph paper — still bears evidence of reordering and revision, underlining Bowie’s meticulousness beneath the improvisational image.

Instruments and Technology

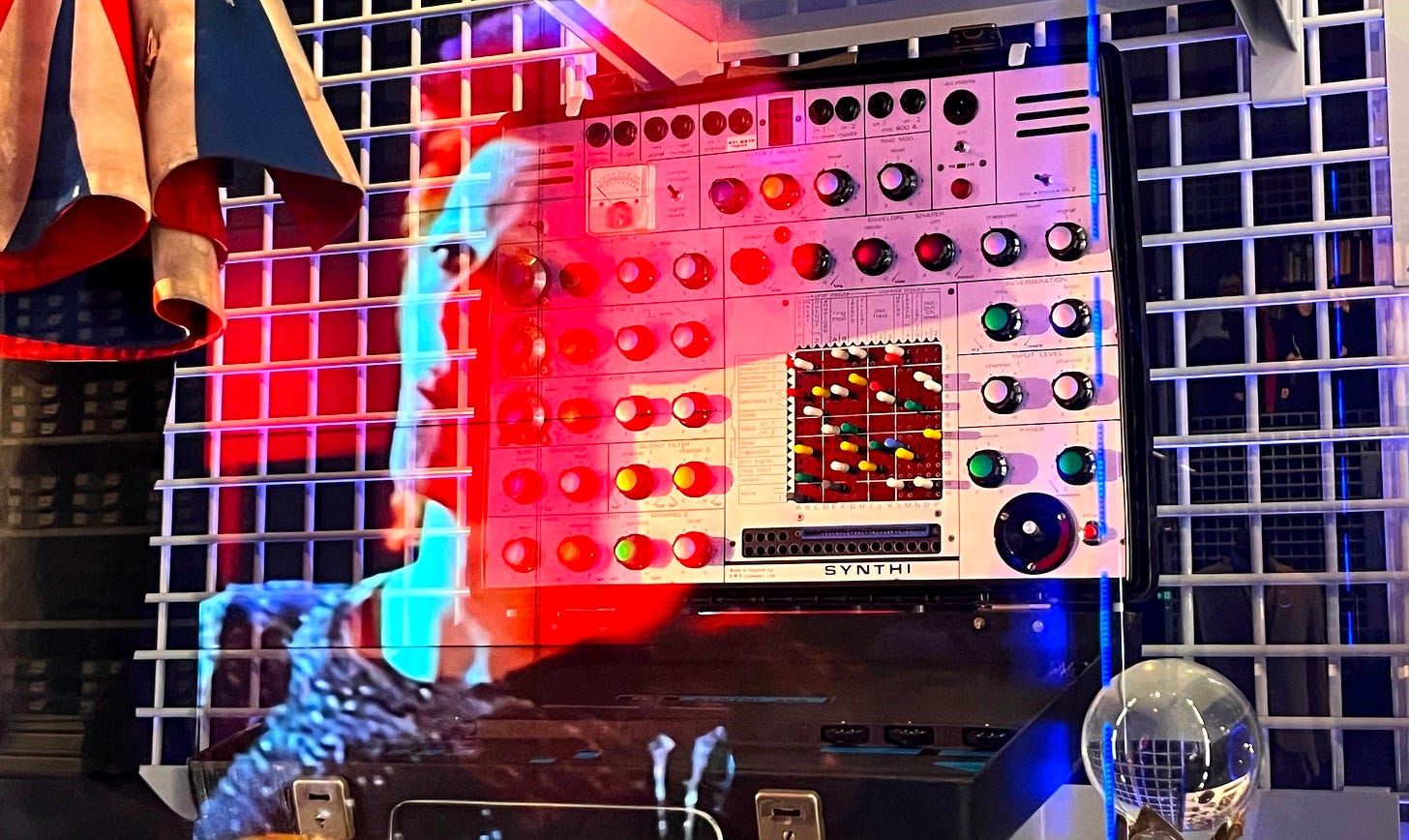

Alongside the manuscripts sits a EMS Synthi AKS, a compact analogue synthesiser central to Bowie’s experimental work of the late 1970s. Used extensively on Low and Heroes, the instrument shows his curiosity about new sound technologies. We also have the Stylophone used on Space Oddity.

Bowie’s open, enthusiastic and experimental approach to technology is often overlooked, but was such a crucial part of his working method, and his creative identities.

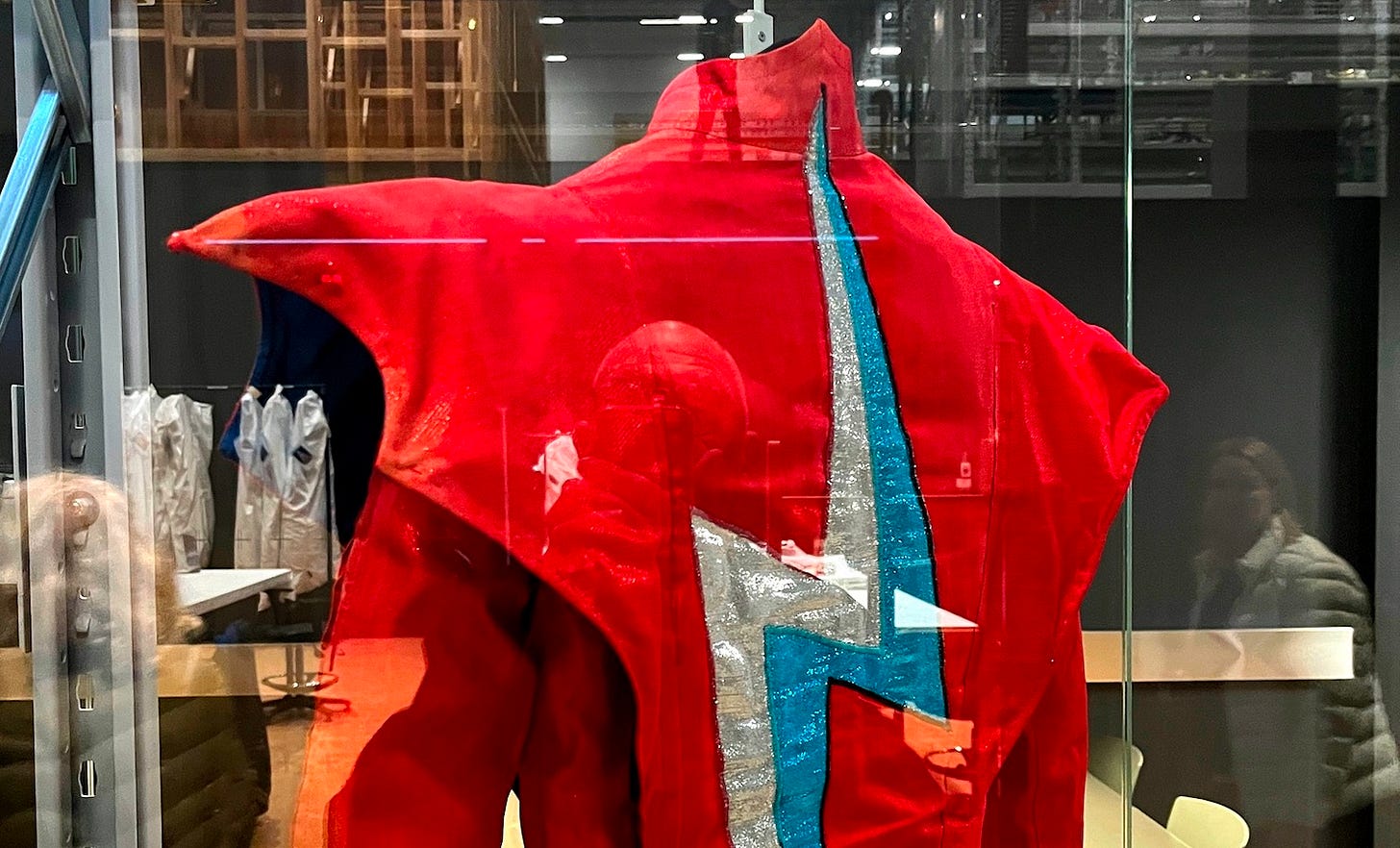

Costume as Language

The Centre’s costume holdings are among its most visually striking. Garments are stored in suspended boxes labeled with designer, tour and year:

Suit designed by Thierry Mugler for Bowie, 1992.

Shirt by Kenny Ho for Earthling Tour, 1997.

Parka as worn in Tin Machine, 1991.

Each marks a point in Bowie’s continual redefinition of identity through clothing.

As you walk into the centre you pass the red lightning-bolt jacket — its angular shoulders suggesting motion, showing how costume operated as both visual design and performance architecture in Bowie’s work.

Research and Preservation

At the Centre’s core is a study room where scholars, students and the public can access archive materials. Next to the space, are projected images and film of Bowie - and of course the music. The space blends display and study, reinforcing the idea that the archive is an ongoing dialogue within a performance space.

The V&A East model of visible storage makes conservation itself part of the visitor experience. Behind glass, conservators catalogue textiles, repair papers, and prepare items for digitization. This transparency highlights how archives are sustained, not simply displayed.

The V&A East Storehouse

The Storehouse is conceived as both museum and working collection — a building-scale rethink of how institutions engage with material culture. Over 250,000 objects from across the V&A’s holdings are visible across four open levels, including sculpture, design, fashion, and decorative arts.

Visitors can trace connections between Bowie’s work and other creative disciplines, from theatre design to digital art, reinforcing his role as a figure who moved freely between them. There’s everything in this space from Byzantine ceilings to Wedgwood prototypes, Bauhaus kitchens to modernist London flats.

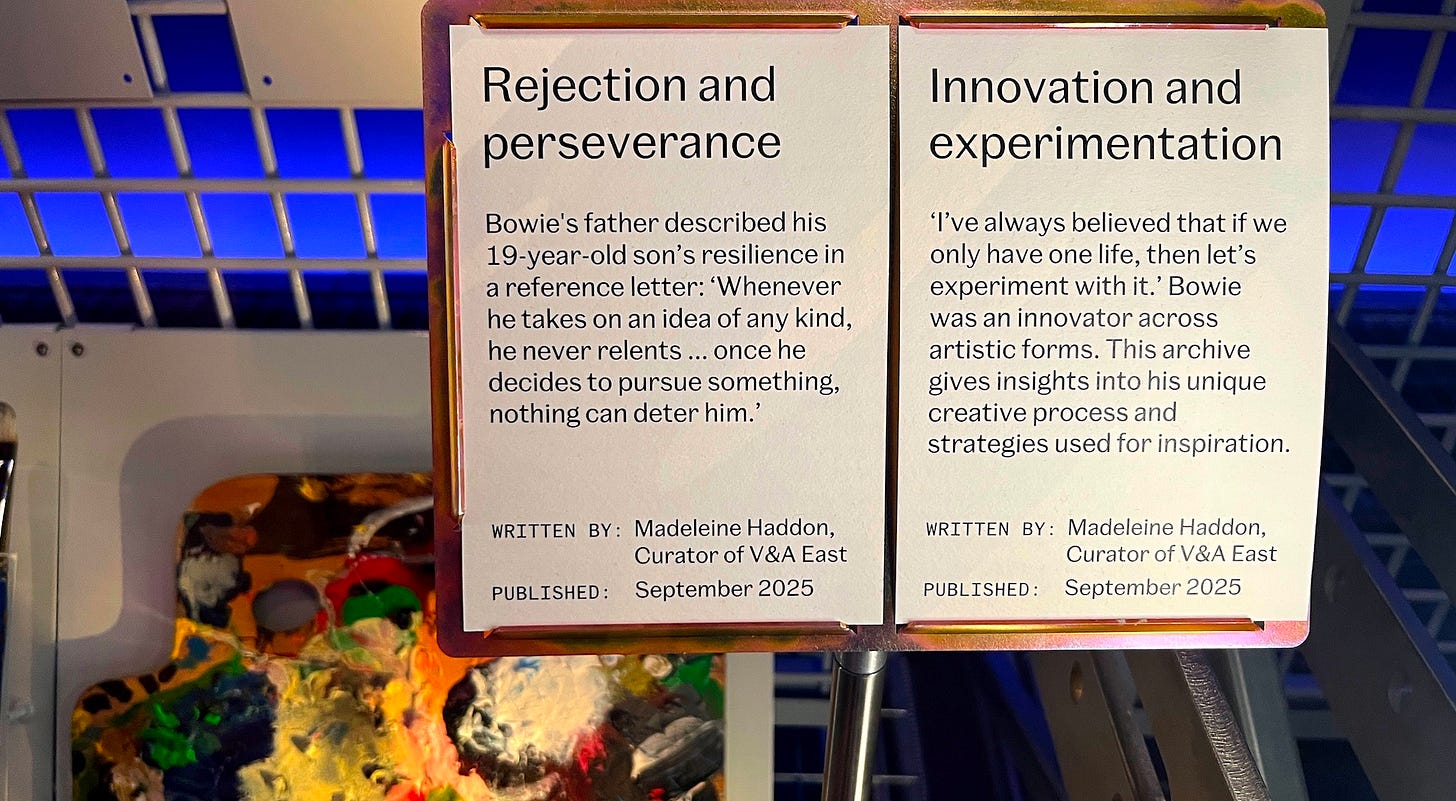

Experiment and Perseverance

Interpretive texts by curator Madeleine Haddon and others frame the Bowie archive. Here we see two quotes, the former from a letter by his father describing Bowie’s persistence in the face of early setbacks; the latter quotes Bowie himself:

“If we only have one life, then let’s experiment with it.”

Together, these statements position the collection not simply as a record of achievement, but as a study of artistic process: persistence, uncertainty and risk as necessary components of creativity. And the Bowie quote stands as a fairly sound philosophy for life.

Context and Legacy

Bowie’s archive, by its breadth, documents the evolution of the late twentieth-century performer as a multi-disciplinary figure: musician, designer, filmmaker, and conceptual artist. In that sense, the Centre is not simply about Bowie himself, but about the creative systems he helped to anticipate — where identity, technology, and art interact and continually redefine one another.

We both loved the Centre and the Storehouse — their open, sometimes almost random transparency, and the way they invite visitors to explore culture without hierarchy. The possibility of requesting items from this vast archive to study firsthand feels almost revolutionary: a direct encounter with creativity.

Both of us thought about our friend Bill Martin, who would have delighted in all the Centre has to offer.

Mike remembers the day in January 1977 when Bill brought home Low — Bowie’s latest release, out that very morning. Like every Bowie record, it sounded like nothing that had come before. Bill played it all afternoon, and we sat listening, amazed by its strange brilliance.

Bill was a little older than the rest of us, and we trusted his instincts about music and art. Mike once asked why he admired Bowie so much. Bill paused for a moment and said, “Because he was the first person to give me permission to be who I am.”

Bill didn’t live to see the later decades of Bowie’s voyage. But he would have loved this place!

Exciting! On my list for my next free London day.

No ordinary museum...no ordinary pop star.

I hope I can get there one day.

Thank you, both, for this insight into what must be an extraordinary experience.