I turn the corner onto Carnaby Street, and the world shifts. It’s a kaleidoscope—everything pulses. The breeze catches the hem of my Mary Quant minidress. Not a real one, obviously—not on my wages. It’s the one Mum helped me run up on her old Singer. I tug it down a little, laughing at myself. Who cares? Here, no one judges. Not like back home.

Shop windows explode with colour. I’ve never seen so much: paisley shirts hung like flags, mannequins in PVC dresses the shade of ripe limes, mod jackets with collars sharp enough to cut glass. A boy in a velvet cape brushes past, smelling of patchouli and Woodbines.

Paperback Writer blasts from Lady Jane, and I nearly collide with a girl in a pixie cut, kohl-rimmed eyes, and red patent boots. She’s daring the world to look at her. Like we all are. Look at me. Because this is our world—our future. We are the future. These clothes, this music. It belongs to us. This is our city. And there’s nowhere else like it on earth.

In 1960, Carnaby Street was a down-at-heel corner of Soho—home to the rag trade and strip clubs. Just four years later, it had become the epicentre of world fashion. Swinging London may have been a media invention, but it captured a real cultural shift. London—Soho in particular—was transformed into a symbol of youthful rebellion, creativity, and modernity.

The Beatles both reflected and accelerated this transformation. It was a moment when Britain began stepping out from under America’s cultural shadow, reshaping its influences into something distinctly its own. London emerged as a rival cultural capital.

What we often overlook, looking back from the 21st century, is the sheer speed of that change—and how close it was to the hardships of the postwar years. “Did you have a gramophone when you were a kid?” an American journalist once asked George Harrison. “A gramophone?” he replied. “We didn’t have sugar.”

An office in town

Brian Epstein rapidly outgrew the desk space that Dick James had given him, and early in 1963 rented offices on the second floor of 13 Monmouth Street in Covent Garden. He lasted little more than a year here, in part because by this time the Beatles’ fan club alone was taking up nearly all the second floor, and because a better image was required, given that the ground floor was a sex shop.

The fifth floor of Sutherland House at 5-6 Argyll Street, right next to the London Palladium was ideal and became the London HQ for Epstein and his NEMS Enterprises from March 1964, just after the band had conquered the US. The new offices enabled him to move twenty five staff down from Liverpool. NEMS acted as booking agent, promoter and manager for The Beatles and their other acts such as Gerry and the Pacemakers, Cilla Black, Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas and, for one year, the Moody Blues. All of The Beatles’ UK and world tours were organised from here until the end of touring in 1966. The band were regular visitors to Sutherland House, often doing press conferences there.

Act naturally

The Beatles' four films—A Hard Day’s Night (1964), Help! (1965), Yellow Submarine (1968), and Let It Be (1970)—were instrumental in shaping their mythology and fame. A Hard Day’s Night captured their charisma, humour, and presented albeit exaggerated identities. Help! built on this further and - in the days before colour TV - presented them in technicolor for a global audience. Yellow Submarine elevated these identities to mythical proportion while Let It Be stripped this away to reveal some authenticity and emotional depth. Each film contributed to their evolving image, ensuring their cultural impact extended far beyond music.

All these films were made in London, delivering on a contract with United Artists agreed by Brian Epstein in October 1963 at the movie company’s offices just two blocks north of Soho at 37-41 Mortimer Street. All four were premiered at Soho’s largest cinema - the London Pavilion on Piccadilly Circus. Originally built as a music hall in 1859, it was rebuilt as theatre in 1885, from which the current structure dates. Not only were all four movies premiered at the London Pavilion, but How I Won The War, starring John Lennon was also premiered there in October 1966.

Relax and float downstream

The use of LSD expanded The Beatles’ artistic horizons, leading to more experimental sounds, and influenced their lyrics, fostering themes of introspection, spirituality, and surrealism. And they first experienced it on a visit to the Ad Lib Club - a nightclub on the fourth floor of 7 Leicester Place above the Prince Charles Cinema in Soho. Beatles biographer Mark Lewisohn describes it as the club 'most strongly associated with The Beatles'.

They decanted to the club following the premiere of A Hard Day's Night at the nearby London Pavilion on 7 July 1964, and Ringo proposed to Maureen Cox here the following January.

The Beatles had their own table at the club, and according to John Lennon it was one of the few places they felt they could visit without being bothered. That is probably why John and Cynthia Lennon, George Harrison and Patti Boyd visited the Ad Lib on 8 April 1965 after they discovered that their coffee had been laced with LSD at a dinner party at their dentist’s house.

It was their first experience of the hallucinogenic drug. As George later described: “We went up into the nightclub and it felt as though the elevator was on fire and we were going into hell (and it was and we were), but at the same time we were all in hysterics and crazy.”

A funny sound

It could be argued that Britain’s interest in world music was sparked on 5 April 1965, in Twickenham, west London. On that day, The Beatles were at Twickenham Film Studios, filming the Indian restaurant scene for their second movie, Help!

As George Harrison recalled in 1992: “We were waiting to shoot the scene in the restaurant when the guy gets thrown in the soup, and there were a few Indian musicians playing in the background. I remember picking up the sitar and trying to hold it and thinking, ‘This is a funny sound.’”

The film’s flaws—its casual racism and cultural ignorance—are unmistakably products of their time. While Help! treats Indian culture as an exotic backdrop, it nonetheless marked the beginning of Harrison’s deep engagement with Indian music and spirituality—one that became increasingly authentic and respectful over time.

Sometime between August and October 1965, Harrison bought his first sitar from Indiacraft, a gift shop at 51 Oxford Street—now a Londis convenience store, just around the corner from Soho Street. Though the instrument was basic, it set him on a path that soon led to lessons with Ravi Shankar, one of India’s greatest classical musicians.

Before beginning formal training, however, Harrison brought the sitar into Abbey Road Studios. On 12 October 1965, he used it during the recording of Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown), introducing the instrument to Western pop music. Other bands soon followed—The Rolling Stones with Paint It Black, The Kinks with See My Friends—and the sitar became a symbol of the psychedelic 60s.

Harrison’s growing fascination with Indian music and spirituality would come to define much of The Beatles’ later work, particularly on Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, where Indian classical influences blended seamlessly with Western psychedelia.

His embrace of Hinduism and meditation inspired many young Britons to explore Eastern philosophies. The ripple effect was huge: the rise of yoga, vegetarianism, and transcendental meditation in mainstream British culture can be traced, in part, to Harrison’s influence. His commitment to Indian music culminated in the 1971 Concert for Bangladesh, further elevating its profile on the global stage.

When George Harrison stepped into a Soho gift shop to buy that sitar, it wasn’t just a musical curiosity—it was the beginning of a cultural bridge. By weaving Indian traditions into Western pop, The Beatles helped dissolve musical and cultural boundaries, opening Britain—and much of the West—to global sounds and ideas.

Making a spectacle

John Lennon filmed a sketch at the entrance of Broadwick Street gentlemen’s toilets, just off Berwick Street, for the Peter Cook and Dudley Moore BBC comedy show Not Only… But Also on 27 November 1966. While these toilets have been closed for some time, the distinctive entrance remains. He plays a doorman at the fictional Ad Lav nightclub - a spoof on the Ad Lib Club. Filmed in the middle of recording sessions for Strawberry Fields Forever, it was his first public outing in wire-framed glasses. Peter Cook plays the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and the sketch was broadcast on BBC One on 26 December 1966. We have a fuller story that details the whole day.

Making a film

In September 1967 The Beatles were away filming Magical Mystery Tour. This included one day’s shooting at Raymond Revuebar strip club on Walker’s Court in Soho. It took eleven weeks for their ten hours of footage to be edited down into a 52 minute film. It was at Norman’s Film Productions on the second floor of 76 Old Compton Street where the editing was done.

Every day Paul McCartney would join editor Roy Benson at the editing studio which is next to the corner with Wardour Street. According to Beatles’ PA Peter Brown “Each Beatle had a say about the film, and it was edited and reedited and tinkered with a thousand times. Often it was changed back and forth four times in the same day, with Paul countermanding John’s suggestions of that very morning.”

It was in this editing suite that they hosted Rosie. Billy Davis, a Soho fixture known as Rosie, was a flamboyant street performer and semi-vagrant, probably in his sixties. Each morning, he adorned himself with carnations—one behind each ear and more in the buttonholes of his tattered army surplus coat. His signature act involved standing in the middle of the road, balancing an empty wine bottle on his head while belting out old music hall tunes, indifferent to the traffic chaos he caused.

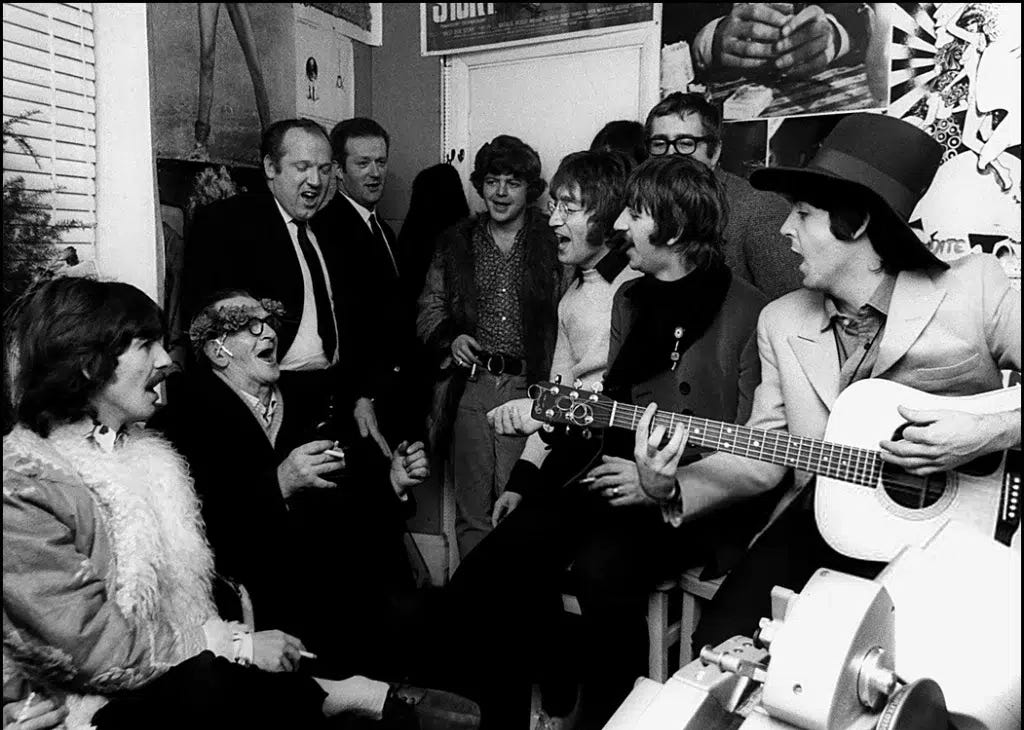

The Beatles befriended Billy and invited him up to their editing suite for a singalong, seen in the photograph below. They were so enamoured by him that a year later, he appeared in the Hey Jude promo film, standing by Paul at the piano and seemingly conducting the band during the fade-out.

A Nice evening

It was after one of their all day editing sessions that Lennon and McCartney gave an unexpected lift to an upcoming new band. From The Who, David Bowie, Pink Floyd to The Sex Pistols, The Damned and beyond, the Marquee Club at 90 Wardour Street - little more than a one minute stroll from Norman’s Film Productions - played a unique and vital role in British music. As well as a music venue, the Marquee also had a small recording studio. The Beatles never performed at the club, but in October 1965 they used the studio to record the group’s annual Christmas message to their fan club members. According to a recent published account, their ad libbed exchanges around a piano generated twenty six minutes of material, none of which was considered suitable for release.

On 24 October 1967, the two Beatles had spent a day editing the film, with the next day scheduled for recording The Fool on the Hill up at Abbey Road. That evening Jimi Hendrix was playing at The Marquee, supported by a new band that was gaining a strong reputation for their theatrical performances. Along with Keith Emerson on keyboards and Brian Davison on drums, Lee Jackson was bass player in The Nice. According to Jackson, after their set “We walked into the dressing room and there was John Lennon and Paul McCartney. They told us, ‘We’ve heard about you buggers. You are fucking good, aren’t you?’”.

Submarine in Soho

65-66 Dean Street, Soho, may appear unremarkable, but from the summer of 1967 for a year, it was the creative hub where TVC London brought Yellow Submarine to life. This groundbreaking animated feature revolutionised animation, blending psychedelic artistry with technical innovation. German illustrator Heinz Edelmann’s bold, surreal designs set the film’s unique visual tone, while the production team—often gathered at the nearby Dog and Duck pub—worked tirelessly to meet the demanding eleven-month schedule. Despite initial skepticism from The Beatles, the film became their most successful multimedia project, inspiring generations of animators and filmmakers. The full story is here. The clip below reveals the contribution made by hundreds of students from London’s art and design schools in completing the film.

The Bag O'Nails

Paul McCartney often ate at The Bag O'Nails club at 9 Kingly Street after recording sessions, many times accompanied by Mal Evans. He met Linda here for the first time. It was a club that was popular with musicians, and was where the Jimi Hendrix Experience first performed in the UK. Jimmy Scott was also a regular at the club, as Paul McCartney explains: “I had a friend called Jimmy Scott who was a Nigerian conga player, who I used to meet in the clubs in London. He had a few expressions, one of which was, ‘Ob la di ob la da, life goes on, bra’. I used to love this expression… He sounded like a philosopher to me. He was a great guy anyway and I said to him, ‘I really like that expression and I’m thinking of using it…”

Jimmy was hired to play congas on early takes of the song, but it was a recording that created friction — both between Jimmy and Paul and within The Beatles. Jimmy wanted a co-writer credit for the song, while the rest of The Beatles disliked the song, and in particular McCartney’s obsessive perfectionism in recording it. It took 48 takes to produce a version the band was happy with. The early version featuring Jimmy Scott was not used until The Beatles’ Anthology was released in the 1990s. But the song was included on the 1968 ‘White Album’ and released as a single in many countries, climbing to number one in seven of them. A cover version by Marmalade got to number one in the UK. The story of Jimmy Scott and the controversy over this song we deal with in more depth in our separate post.

Trident Studios

Trident Studios was located on St Anne’s Court, an alley that leads between Dean Street and Wardour Street. There’s just a plaque on the wall outside the building that once housed probably the most important independent recording studio in the world. It was here that Ziggy Stardust and other early Bowie albums were recorded, T-Rex did their best work, Genesis and Queen made their marks on prog and glam (along the way the pop video was born), and The Beatles recorded Hey Jude on 31 July 1968, along with a number of other songs from the White Album. Lou Reed’s Walk on the Wild Side was also recorded here, cementing Trident’s reputation for cutting-edge production.

In 1968, Trident was the first UK studio with Dolby noise reduction. While Abbey Road Studios still used four-track, Trident's eight-track machine was a huge attraction for The Beatles. Dear Prudence, Honey Pie, Savoy Truffle and Martha My Dear were also recorded. The following February, the first recordings for what would become Abbey Road were laid down at Trident - I Want You (She's So Heavy) with Billy Preston, and in October Plastic Ono Band recorded "Cold Turkey" with Eric Clapton.

Recorded as part of George Harrison’s 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass, My Sweet Lord was a labour of love. The core tracks were recorded at Abbey Road Studios with a star-studded lineup that included Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton, and Gary Brooker. However, Harrison envisioned a choral effect for the backing vocals, credited on the album to the George O'Hara-Smith Singers—an overdubbed “choir” of Harrison himself, created at Trident Studios, then the only 16-track studio in the UK. With sales of around ten million it remains one of best selling singles of all time. The video below was filmed at Trident.

Apple Corps

Just over Regent Street from Soho, and along Vigo Street, 3 Savile Row was the HQ for Apple Corps - The Beatles’ multimedia company. The building costs them £500,000 and they moved in on 15 July 1968. The idea of Apple was "A beautiful place where you can buy beautiful things… a controlled weirdness… a kind of Western communism"according to McCartney. A recording studio in the basement was used initially for some of their Let It Be album and by other artists until its closure in 1975. The Beatles performed in public for the final time on the roof of the building on 30 January 1969 which was shown most recently in the Get Back TV films. Apple included divisions in records, film, electronics, books and the studio. There was even a tailoring division. It promised a new way of doing creative business, that gave more control to the artists.

Many books have been written that essentially argue that it was in this building that the dream of the Sixties turned into a nightmare of litigation, and demonstrate the insanity of putting artists in control of anything. Now, perhaps we’re biased, but we we reckon that while Apple Corps had its obvious failings in the short term, in the longer term Apple has a highly positive legacy.

The company haemorrhaged money due to a lack of structure and poor financial oversight. It was envisioned as an artist-friendly, anti-corporate enterprise, but this led to chaos rather than creative utopia. Overlaying this, 3 Savile Row became a battleground for The Beatles’ personal and business tensions, particularly between Paul McCartney and the other three after they appointed Allen Klein as manager.

But despite its business failings, Apple Corps created a model of artistic control that inspired later musicians to establish their own labels (e.g., Prince’s Paisley Park). Apple Records gave us the last four Beatles’ albums and some of the best solo work. It also gave a platform to artists like Billy Preston, Badfinger, Mary Hopkin, and James Taylor. Today, Apple Corps is a well-run, highly profitable entity managing The Beatles' catalogue, and innovative projects like The Beatles: Get Back documentary.

Steve Jobs once said “my model for business is The Beatles” and as a fan he named his own company Apple, which of course created a great deal of work for lawyers. However, what he meant by this is hugely significant - and beyond the scope of this post (although one of us has given lectures on this very subject!). Suffice to say, one legacy of this building is the phone in your pocket.

While Apple Corps failed as a 1960s utopian experiment, it succeeded in securing The Beatles’ cultural and financial legacy—and created some of the most astonishing, wonderful and influential music of the twentieth century.

Songs for a tailor

Alongside The Beatles, Terence Stamp, Twiggy, David Bailey, and Sandie Shaw, Tommy Nutter was another working-class British icon who helped define the style of the 1960s. A North London boy who once trained as a plumber, Nutter went on to revolutionise the Savile Row suit.

With financial backing from singer Cilla Black and Apple Records' Managing Director Peter Brown (name-checked in The Ballad of John and Yoko), Nutter launched his tailoring business just up the road from Apple at 35a Savile Row in 1969. He shaped the late-period Beatles look, designing the cream corduroy suit John Lennon wore for his wedding to Yoko Ono in Gibraltar and outfitting three of the four Beatles for the Abbey Road album cover. Nutter died in 1992 due to an AIDS-related illness, leaving behind a legacy of innovation in British tailoring.

I fought the law…

The Courthouse Hotel at 19–21 Great Marlborough Street was once the Great Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court, a venue with a colourful and often notorious legal history. Charles Dickens worked there as a reporter, and years later, Oscar Wilde took the Marquess of Queensberry to court on the very same premises. Celebrity drugs busts became almost an annual tradition, drawing in names like Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Francis Bacon and Johnny Rotten.

On 17 January 1970, eight "indecent" lithographs by John Lennon were seized by police from the London Art Gallery on Bond Street, where they were part of an exhibition by the former Beatle. The artworks were from Bag One, a series Lennon had created the previous year, chronicling his wedding and honeymoon with Yoko Ono, including their now-famous bed-in for peace.

Prosecution witnesses included an elderly accountant from Wandsworth, who testified that he had "felt a bit sick that a man should draw himself and his wife in such positions." He expressed particular horror at seeing "Yoko in the nude, with rather exaggerated bosom with apparently somebody sucking a nipple."

Three weeks into the trial, magistrate St John Harmsworth dismissed the case, ruling that the gallery did not constitute a “public place” under the terms of the relevant legislation. The Metropolitan Police later confirmed that the gallery was free to reopen the exhibition, which it did—to considerable public interest. (I visited myself, but being under 18, wasn’t allowed to enter.)

As critic David Lee later observed:

"I think the failure of that trial is incredibly important because it really marks the point at which youth culture has won and the establishment has lost. They tried very hard to victimize many of the more important major characters of the sixties—Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were others—and they failed in all cases."

Now the workers have struck for fame…

Sex, music, cinema, fashion, food, theatre—and, of course, politics. Soho had it all, and it had it before anywhere else did.

Communism itself took shape in a Soho pub’s function room, where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels first launched The Communist Manifesto. Marx, who lived at 28 Dean Street, not only ended up on the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band but also inspired an ideology that John Lennon would embrace.

Soho’s radical political roots run deep, partly shaped by waves of political refugees who settled there, including the Marx family. In the 19th century, the Red Lion pub on Great Windmill Street and Eclectic Hall on Denmark Street buzzed with activist gatherings. By the 20th century, clubs like Amy Ashwood’s on Carnaby Street became hubs for pan-African activists envisioning a post-colonial future. Later, the Partisan Coffee House on Carlisle Street emerged as a meeting place for the New Left, galvanized by opposition to the Soviet invasion of Hungary in the 1950s.

In 1970–71, Lennon aligned himself with the International Marxist Group (IMG), a Trotskyist faction tied to the Fourth International. In a 1971 interview with Red Mole editor Tariq Ali, Lennon and Yoko Ono laid out their beliefs: “The workers can start to take over. Like Marx said: ‘To each according to his need.’ I think that would work well here… We should be trying to reach the young workers because that’s when you’re the most idealistic and have the least fear… We can’t have a revolution that doesn’t involve and liberate women.”

Two anthems emerged from this period: Power to the People and Imagine. Nine years later, just before his death in New York, Lennon reflected: “In England, there are only two things to be, basically: You are either for the labour movement or for the capitalist movement. Either you become a right-wing Archie Bunker if you’re in my class, or you become an instinctive socialist, which I was. That meant I think people should get their false teeth and their health looked after, all the rest of it.”

MPL Communications

Since 1970 number one Soho Square has been home to MPL Communications, Paul McCartney’s music publishing company. Along with managing McCartney’s business interests, MPL has developed into one of the world's largest independent music publisher. Blue Suede Shoes and That’ll Be The Day are among the songs owned by MPL along with more than 3,000 others including the catalogues of Buddy Holly and Carl Perkins. In the basement is a recording studio that is a replica of Abbey Road’s No. 2 studio.

And in the end…

Liverpool gave them their roots. Hamburg honed their craft. Soho was where the alchemy happened.

Soho was where The Beatles became The Beatles—a cultural phenomenon that marked a turning point in British social and cultural history. As we’ve argued, this wasn’t just about four young men. It was about all of us.

Finally…

Here’s some music.

We're also planning a guided walking tour — The Beatles & Soho — to complement this series, part of our wider collection of musical Soho walks. Details in our next post.

Buy us a coffee

We love sharing our writing and research freely — and we want to keep it that way. Our hope is that these posts spark your interest and give you a good read.

If you’ve enjoyed what we do and would like to support the time, thought, and research that goes into it, we’ve added a Buy Me a Coffee button. We really appreciate your support.

Wow, so much detail. I look forward to listening to the playlist.

Before I started reading this set of posts, I thought of myself as something of a Beatles expert. On finishing it I now realise I'm something of a novice :-) A key moment came when I started the final part thinking that I bet Mike doesn't remember the Ad-Lav cameo by John Lennon. Dohhh! He remembered. What was I thinking??

Thank you Mike, for a fascinating, meticulously researched and uplifting series of posts on the Fab Four. I'll never look at Soho the same way again.