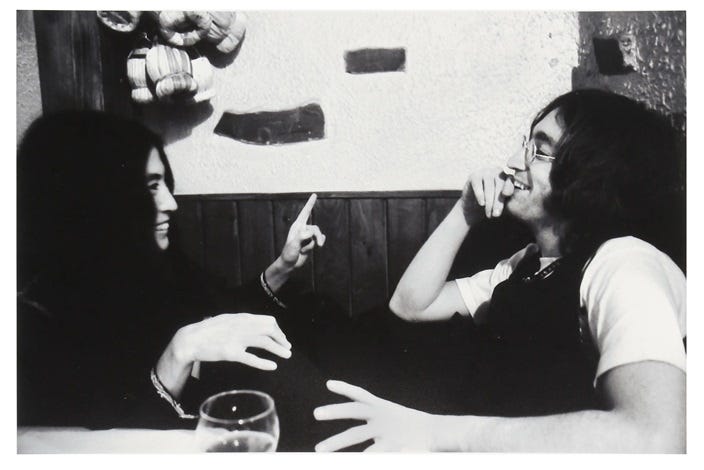

I bought my copy of John and Yoko’s Two Virgins album in 1969, and I had to sell half my singles collection to fund the purchase. The photo above actually shows the back cover. If you’re not familiar with the album, the front cover shows both artists, naked, facing the camera. It’s not that I’m particularly prudish about showing the front cover, but I assumed most people idly scrolling through Substack probably wouldn’t fancy suddenly coming face-to-face with the last turkey in the shop.

I think I’d cobbled together ten bob of Christmas money, added half a crown I’d earned washing the car, and whatever I’d made selling singles at school. Albums back then cost around 37/11, and most of my savings ended up as small-denomination coins jingling in the bottom of my school bag. I bought Two Virgins at the Record Room, a small shop on Chequer Street in St Albans run by Mark Greene. Donovan, The Zombies, and others reckoned it was the best record shop outside London.

Back then, we didn’t have chain stores. We had people who loved music, wanted to share it, and aimed to make an honest profit in the process. Mark knew his music, and over the years, a fair bit of my pocket money went over his counter—generally in small-denomination coins.

Mark’s brother, Sol, ran the town’s drapery business around the corner. Both shops had character, a direct reflection of the Greenes’ genuine passion for what they sold. The day I bought Two Virgins, I’d scoured the racks without success and went to the counter to ask if Mark had it.

“Yes, I know I’ve got one copy of it,” he said, searching the shelves behind him. After several minutes, he went down to the cellar. He returned empty-handed, visibly rattled that it had been misfiled. Shouting to his assistant, he said, “Mac, I can’t seem to lay my hands on Two Virgins!” He seemed genuinely puzzled by the stifled laughter of the schoolboys hanging around the shop.

Eventually, Mark found the album. He laid it on the counter, stared at it, and sucked his teeth.

“Look, I can’t sell you this.”

“Why not?”

“I can’t. Your parents would have me arrested.”

The cover had provoked complete outrage at the time—and that was just within The Beatles. Once his bandmates relented, Lennon found that EMI wouldn’t touch it. In the UK, Track Records reluctantly pressed only 5,000 copies. No record plant agreed to package the album, so Beatles fans were hired to sleeve it by hand. The fact that it had made it to Mark Greene’s counter was a miracle. And now it seemed tantalisingly out of reach.

“Oh, come on. I’ve saved up for this for weeks.”

More teeth-sucking. His fingers drummed on his chin.

“I’ll sell it to your mum or dad, but not to you.”

A deal was struck. The next day, accompanied by a parent, I finally bought Two Virgins.

I wasn’t sure what I was expecting, but half an hour of tape loops, random sound effects, background chatter, Yoko’s raw vocals and unstructured experimentation was a lot for thirteen-year-old ears. They recorded it through the night and, reportedly, consummated their relationship at dawn.

Sometimes you really have to work a bit at music to appreciate it. But was it worth sacrificing half my singles collection and causing Mark Greene an ethical quandary? Absolutely. And here’s why.

Get back

Let’s get back to the 1960s… Just three years before Two Virgins was recorded, a typical Beatles album comprised some brilliant self-written love songs, a few competent fillers, and a brace of rock and roll covers. By 1968, they were working on what became The White Album.

This sprawling, dazzlingly eclectic masterpiece—spread over four sides of vinyl—is not only the band’s finest but stands as one of the defining works of twentieth-century music. I was twelve when I first sat down with my mum and dad to listen to it. I remember being utterly mesmerised by its sheer breadth and audacious risks—like John, Yoko, and George’s eight-minute musique concrète. It’s the one Beatles album I revisit often, not out of nostalgia, but because I hear something new every time.

The Beatles spearheaded this idea of musical progress, taking us on a journey with them. They brought what we now call world music into their work, explored new technologies, blurred genres, and reflected the momentous changes happening in the world around them.

The years 1968–1969 were pivotal for both music and politics. In Europe, we had the Prague Spring, the Soviet invasion, a million Parisians marching in May, and De Gaulle fleeing France in fear of revolution. Italy’s Hot Autumn saw millions on strike over a sustained period of industrial conflict. In Britain, there was Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech, while police brutality in Derry sparked the Civil Rights Movement. In the US, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy coincided with the civil rights and anti-war movements.

It was a fractured and conflicted time—idealism clashing with cynicism, unity with disunity. But it was also ambitious: for change, progress, and to boldly go where no one had gone before. Like the Moon. The White Album reflects this ambition, as does much of the period’s music.

Experimental Frontiers

Many musicians began to break away from the limitations of blues-based rock. Advances in recording technology and political upheaval pushed them toward new frontiers. Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma (1969) fused musique concrète with rock instrumentation. Soft Machine’s Volume Two (1969) offered a Dadaist jazz-rock fusion. King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King (1969) blended jazz, rock, classical, and avant-garde influences.

Meanwhile, in Germany, Can’s 1968 debut album was so experimental it wasn’t released until 1981. Their follow-up, Monster Movie (1969), combined rock, free jazz, and tape editing. In the US, artists like Velvet Underground, Miles Davis, Frank Zappa, and Captain Beefheart were also pushing music into uncharted territory.

In Britain, one album embodied the experimental spirit of the age. Recorded in 1968 and released in 1969, White Noise’s An Electric Storm—which I found in Mark Greene’s sales rack a year later—paved the way for krautrock, ambient, and synth-pop. Its soundscapes, rooted in electronic manipulation, tape loops, and early synthesisers, were ahead of their time. At the heart of the experimental ensemble was the wonderful Delia Derbyshire - famed for her work on the Doctor Who theme at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

The Context of Two Virgins

The late 1960s saw many musicians striving to create music that reflected an age of transformation—an era of pushing creative boundaries and embracing new technologies. Yet, John Lennon and Yoko Ono were uniquely positioned to take this further. Their creative partnership brought together two vastly different worlds: Yoko Ono’s avant-garde background, steeped in conceptual art and the Fluxus movement, and John Lennon’s roots in popular music and the countercultural zeitgeist of the time. Ono’s art was built on performance, experimental techniques, and a drive to challenge traditional boundaries, often confronting audiences in the process. Lennon, on the other hand, had a rare ability to connect universally, reaching anyone within earshot of a radio.

Despite their differences, the two shared a vision: to explore art and life with raw authenticity. Ono’s intellectual and artistic circles had aspirations for social transformation, yet struggled to connect meaningfully with the wider public. Lennon, as a Beatle, bridged that gap, embodying an accessibility that gave him a direct line to millions. Together, they created something unique.

The Creation of Two Virgins

The first product of their artistic collaboration, Two Virgins, was conceived as a raw, unfiltered exploration of their relationship and shared creative vision. Improvisational and experimental, it became the inaugural entry in their Unfinished Music series, an ambitious trilogy documenting their lives in a deeply personal way—akin, in some respects, to how people use social media today to share moments of vulnerability and authenticity. Theirs was an experiment in how artists could connect openly with their audience.

For Lennon, Two Virgins marked the beginning of his intentional break from The Beatles, challenging both his own creative identity and the expectations of his audience. For Ono, steeped in the Fluxus ethos, the album exemplified the idea that art was a process rather than a polished, finished product. Years later, she reflected on this difference in creative approaches while discussing her work with her son, Sean:

“Sean has such an energy, which is interesting. John was a bit more emotional… Both John and I come from an emotional, romantic age, shall we say. And I think that this generation—Sean’s generation and his friends—are more, sort of, mathematical. They can think about it from the point of view of trying to make it into something. We didn’t try to make it into something… we just did it. That’s the difference, I think.”

Two Virgins was just one piece of a broader tapestry of activism and creative rebellion. Within the context of their bed-ins for peace, bagism, and The Ballad of John and Yoko, the album stood as a bold statement of equality between two creative forces. Their partnership was groundbreaking in its radical honesty, vulnerability, and mutual respect—a dynamic that was revolutionary in 1969.

Bravery and legacy

The album also came at a cost. The pair endured public vitriol, often in the form of racist and sexist abuse shouted on the streets. Undeterred, they used their fame to challenge the status quo, speaking out against racism, sexism, and war, while championing love, peace, and feminism.

Their collaboration was not only inspiring and enlightening but also resulted in deeply honest music. From Two Virgins to the Plastic Ono Band albums, Imagine, Fly, Sometime in New York City, and ultimately Double Fantasy, their work was propelled by an idealism rooted in their love for each other.

I still vividly recall hunting through record stores in Soho to find an import copy of Sometime in New York City. And I remember the thrill of being there on the day Double Fantasy was released.

London, 8th June 1996

A deafening roar erupted from the crowd as the spotlights swept across the stage and landed on a diminutive figure dressed in black. Yoko Ono. She strode forward with quiet confidence, her presence magnetic, commanding attention before she had even sung a note. Behind her, a group of young musicians gathered in a loose formation, plugging in their instruments and unleashing a surge of energy with the first furious chords. The music was alive, a pulsing heartbeat that seemed to electrify the space. This was London’s Astoria, a small venue on the edge of Soho, demolished two decades later to make way for the Elizabeth Line.

Yoko moved across the stage like a force of nature—sometimes pacing with an intense focus, other times twisting, howling, and screaming into the microphone with raw abandon. Her voice was a weapon, piercing through the layers of sound with an intensity that felt both primal and vulnerable.

The audience, a mix of mainly young fans, members of London’s Japanese community, and a handful of older folk, matched the band’s energy. They swayed, shouted, and moved as if caught in the gravitational pull of the music. Even at a pensionable age, Yoko Ono wielded a rare and powerful magic, holding her audience spellbound for two straight hours.

At her side, her son Sean Lennon and his band delivered a brilliant accompaniment—both jagged and polished, chaotic yet tight. Together, they created a soundscape that was as unpredictable as it was exhilarating, a perfect reflection of Yoko’s fearless artistry.

This wasn’t just a performance; it was a testament to everything Yoko Ono had given to music over the decades—uncompromising honesty, boundless emotion, and the audacity to challenge conventions. In all my years of experiencing live music, only a handful of performances have etched themselves as deeply into my memory—Patti Smith, Nina Simone, Bob Marley, and Yoko Ono. Each brought something that transcended the act of playing music and became a moment of total and utter magic.

And that evening’s sense of musical magic was rooted in the first time I listened to Two Virgins. Yes, it was worth half my singles collection.

‘Last turkey in the shop’ :D I can imagine the looks you got asking for that album!

Fascinating insights, Mike. I watched the film Beatles ‘64 a couple of nights ago, about their first trip to the US to appear on the Ed Sullivan show. Fresh-faced young men. As you say, it’s amazing how their music evolved during the following years.

Great insight Mike. Neatly explains the combined creativity of John and Yoko which I never really understood. I wonder what would have happened if he’d lived.