The other day, sorting through some old boxes in the attic, I found this. David Bowie launched his internet service in 1998, and for a brief period I used it. Bowie viewed the internet as a revolutionary force that would democratise creativity, dismantle old power structures, and redefine art and commerce. While he acknowledged its disruptive potential, he remained optimistic about its ability to empower artists and fans alike.

He wrote in the New York Times “I’m fully confident that copyright, for instance, will no longer exist in 10 years, and authorship and intellectual property is in for such a bashing.” As he said in an interview with the BBC’s Jeremy Paxman "The potential of what the internet is going to do to society—both good and bad—is unimaginable. I think we’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying." In his reply to Paxman, who suggested the internet was just “a tool”, Bowie said “No, it’s not – it’s an alien life form!”

We will never know how Bowie would have navigated the world of AI. But that shouldn’t stop us from speculating by drawing on how he creatively explored previous technologies. Perhaps there are some lessons for us all, whatever creative domain we work in.

David Bowie’s embrace of the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s stands in stark contrast to how many musicians and artists view AI today. While Bowie saw technology as an inevitable, transformative force to be harnessed creatively, contemporary artists are far more divided, cautious, and even hostile toward AI’s role in art.

Bowie’s contemporary Peter Gabriel is one of the very few musicians to see AI positively: “I think you do better if you work with a powerful new tool than just grumble or pretend it doesn’t exist.” Nick Cave takes the opposite view, suggesting that AI is a “grotesque mockery of what it is to be human”.

But we’ve seen this before.

"[It] is the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies… If it is allowed to encroach upon the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of something of a man’s soul, then it will be so much the worse for us!"

The ‘it’ is photography, and the writer is Charles Baudelaire in 1859. His view was a fairly general one in the art community. Painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres forbid his students from using photographs, saying in 1862: "Do not rely on this industrial process; it is the negation of drawing, of style, of truth itself!"

Early critics of photography saw it in terms of mechanical copying, as a soulless pursuit unworthy of art, with the potential to kill painting. Of course, painting was not killed by the camera - it was redefined - and photography realised its potential as art through people such as Man Ray and Cindy Sherman. The technology of photography opened up a whole new area of creative exploration, with artists such as Madame Yevonde developing the technique of solarisation.

Within music itself there is a well documented history of aversion to technological change. John Philip Sousa was an American composer of military marches, and in his day one of the most popular musicians. His 1906 essay on ‘The Menace of Mechanical Music’ took aim at phonographs, which “reduce the expression of music to a mathematical system of megaphones, wheels, cogs, disks, cylinders, and all manner of revolving things”.

Building on his mechanical and soulless critique, Alice Clark Cook, writing in Musical America magazine in 1916, was of the view that recorded music was narcissistic and would erode our brains: “Mental muscles become flabby through a constant flow of recorded popular music,” she asserted, worrying that our brains are reduced to “a complete and comfortable vacuum.”

In the 1950s folk revivalists like Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger promoted acoustic music as more authentic and politically honest as a reaction against the technology and commercialisation of popular music culture. The revivalists distrusted studio manipulation, and indeed some simply drew the line at electricity. When Bob Dylan plugged in a Fender at Manchester Free Trade Hall in 1966, he was met with a cry of "Judas!"

Synthesizers, drum machines, sampling and auto-tune - all these innovations have faced accusations of cheating, being soulless and taking musicians’ jobs away. The Grammy-winning trumpet player Nicholas Payton takes a strong position on sampling: “Hiphop is a predatory art form — and over the years — has more and more become a bastion of musical cannibalism.”

Meanwhile, musicians such as Sly Stone, Wendy Carlos, Stevie Wonder, Bowie, Grimes, Prince, Miles Davis, Björk and others have all been early adopters of groundbreaking musical technologies. Some indeed define themselves in terms of their relationship with technology. As Björk said “I see myself as someone who builds bridges between the human things we do every day, and technology.”

I’m Afraid of Americans

Critical attitudes to technology in music (and culture generally) ebb and flow, and are best seen as a symptom of something more deep rooted. It’s a proxy for existential anxiety. When people fear new tools, they’re usually reacting to deeper uncertainties triggered by other changes in the world. We’re all scared of Trump, so naturally AI is viewed as a dark force.

Without the pioneering technologies of music in the 1960s, there would have been no Phil Spector Wall of Sound, no Brian Wilson’s Pet Sounds, no Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper. And throughout the swinging sixties and the summer of love the world loved it all, along with Wendy Carlos’s ground breaking Switched on Bach. In contrast, AI is being introduced during a time of precarious gig work, climate collapse, the rise of the new right and eroding trust in institutions. The pattern seems to be that technophobia amplifies when people feel powerless and under threat.

It is also amplified when elites feel threatened. 19th-century painters dismissed photography because up to that point they had a monopoly over portraiture. Late twentieth century session musicians criticised samplers and drum machines because it threatened their livelihoods. And today’s publishing industry resists AI because it disrupts their curation monopoly. Of course in all cases the criticisms were framed in terms of quality and dehumanising culture - but it mainly boils down to money and power.

But of course AI isn’t simply just another case of technophobia. It introduces some unique issues and concerns of its own. In terms of scale and automation, AI can generate content much faster than past tools, raising fears of mass displacement. Unlike a drum machine, AI models are trained on existing works, leading to copyright disputes and a whole debate over ethics and the issue of authorship. This is linked to a final concern. AI can mimic human styles too well, often far better than humans, making it harder to distinguish human-made from AI-made work.

We are in a fundamentally new territory here: AI doesn’t just aid creativity, it simulates it, which challenges us to rethink what creativity even means. The debate isn’t just about the tool; it’s about how we define creativity, authorship, and value in the digital age.

If AI can generate technically proficient art, music, or writing, then the role of the human creator must evolve beyond mere execution. Cultural relevance, curation, and meaning-making become the new frontiers of creativity.

A Small Plot of Land

In my very partial and subjective reading of views on AI within Substack’s writing communities, the critics are most vocal. There is the ethical backlash over copyrighted training material, a disdain for the ‘soulless’ style of AI writing, and the fear over professional obsolescence. However, the algorithms of social media are such (and Substack is a social medium) that these views are amplified.

Conversations off-line suggest that something else is going on too. Working heads down, there are quiet experimenters patiently hacking the system. Beneath the noise, many writers are tinkering, using DeepSeek (other AI platforms are available) for brainstorming, beating writer’s block, editing and exploring how to use it as a creative partner. Few are open about using AI for fear of backlash. As one anonymous novelist told The Guardian: “It’s like admitting you use steroids.”

As in most things in the world today, views are clearly polarised, which is distinctly unhealthy. We should accept that there are two types of ‘creatives’ - one type adheres to the ‘traditional’ craft of their creative practice, while another explores new ways of doing things.

To understand how creatives respond to this new terrain, consider Brian Eno’s metaphor: some artists are farmers, others are cowboys.

The farmer tends the known land—slow, methodical, invested in mastery. They value tradition and depth, trusting that art comes from sustained labour.

The cowboy rides into unfamiliar territory—curious, risk-taking, often improvising with tools they haven’t fully mastered.

Today, you can see this split in how writers, musicians, and artists engage with AI:

The farmer is the novelist who refines each sentence over months, trusting their inner editor more than any algorithm.

The cowboy is the poet who uses DeepSeek to generate wild stanzas, sifting through randomness for unexpected sparks.

Both are valid. Creative ecosystems need both. Cowboys expand the map; farmers make it fertile. It’s not a choice between right and wrong, it’s a choice between tempo and terrain.

Absolute Beginners

As David Bowie once said, in a very different context, “we’re on the cusp of something exhilarating and terrifying.” Technology doesn’t dictate our future—we do. Its impact on culture and creativity isn’t pre-determined; it’s contested, shaped, and steered by human intention. The real question is: how might we engage with it in ways that serve, rather than subvert, our creative values?

Take portraiture as an example. A traditional painter might spend weeks capturing the likeness and soul of a sitter—layering brushstrokes, building texture, returning again and again to refine nuance. A photographer, by contrast, might complete a session in just a few hours, delivering polished images within days. And photography adds something painting can’t: the power of the decisive moment. Think of Alberto Korda’s iconic image of Che Guevara—captured in a split second during a memorial service. A single frame. Timeless impact.

Technology has always accelerated the speed of execution. Now, with AI, we’ve reached another threshold. The time from concept to product is shrinking, sometimes to nothing at all. AI can generate infinite variations in seconds. But it can’t choose what matters. That’s our role.

Human creators bring judgment, context, and meaning. While AI handles how something is made, we focus on the why. It can replicate style, but it can’t invent intent. It can suggest form, but only we can infuse irony, subversion, or emotional truth. We curate, shape, and imbue AI outputs with resonance drawn from lived experience.

So, in this new creative landscape, what metaphor best captures the artist who embraces technology not with fear, but with Bowie’s spirit of experimentation and play?

Kooks

Brian Eno once suggested that modern artists are becoming curators: DJs of culture. But there’s a limitation to that metaphor: a DJ selects from a fixed library, remixing what already exists. The AI-augmented creator, on the other hand, doesn’t just select or arrange: they can conjure entirely new ingredients on demand.

So let’s switch metaphors.

Picture instead the creative as a kook: an avant-gardist, experimental, rule-bending chef. A great cook knows which ingredients are fresh, which are tired, and where to find something surprising. Their recipes are more than instructions: they’re expressions of taste, philosophy, vision. They adapt to constraints, seize on accidents, and always think about presentation in its widest sense. They know how to throw a good dinner party.

And no one judges a cook for using a food processor or not making their own pasta from scratch. What matters is the result: did it nourish, did it delight, did it make people feel something? In the same way, creatives who use AI aren’t defined by the tool, but by what they do with it. No one will fault a writer for using an AI to brainstorm, unless the final work is shallow or soulless. Meaning is still our job.

Of course, as with every previous technological disruption, the creative world is splintering into tribes.

The Purists reject AI outright, clinging to the handmade as a political and aesthetic stance. Like the folk revivalists of the 1950s, they value tradition and resist the commodification of art.

The Hybrids treat AI as a tool—one among many. They might use it to generate drafts, spark ideas, tweak language—but the final product bears their unique signature.

The Kooks are the experimenters. They embrace AI as a co-creator, collaborating, even letting the machine take the lead. They’re playful, anarchic, open to the weird.

These divisions aren’t just stylistic—they’re ideological. And they’re already fuelling debates as passionate as the one that erupted when Dylan went electric.

But progress—real, cultural progress—depends on those who bridge these tribes. The ones who defy categorisation. The ones who, like Bowie, don’t choose between acoustic and electronic, authenticity and artifice, Brecht and Brel—but instead revel in the tension between them.

Bowie understood that experimentation invites failure. One of the other things I found in our attic was Jump, his short-lived interactive CD-ROM. Anyone remember playing that? I did—for a short time. Bowie later admitted: “I hated it. I absolutely loathed it... There were aspects of it I thought had potential, but... the idea of anybody using it interactively [was] a joke.” CD-ROMs were the evolutionary dead end of digital culture, but a worthwhile one. Many of us learned from experimenting with that soon redundant format.

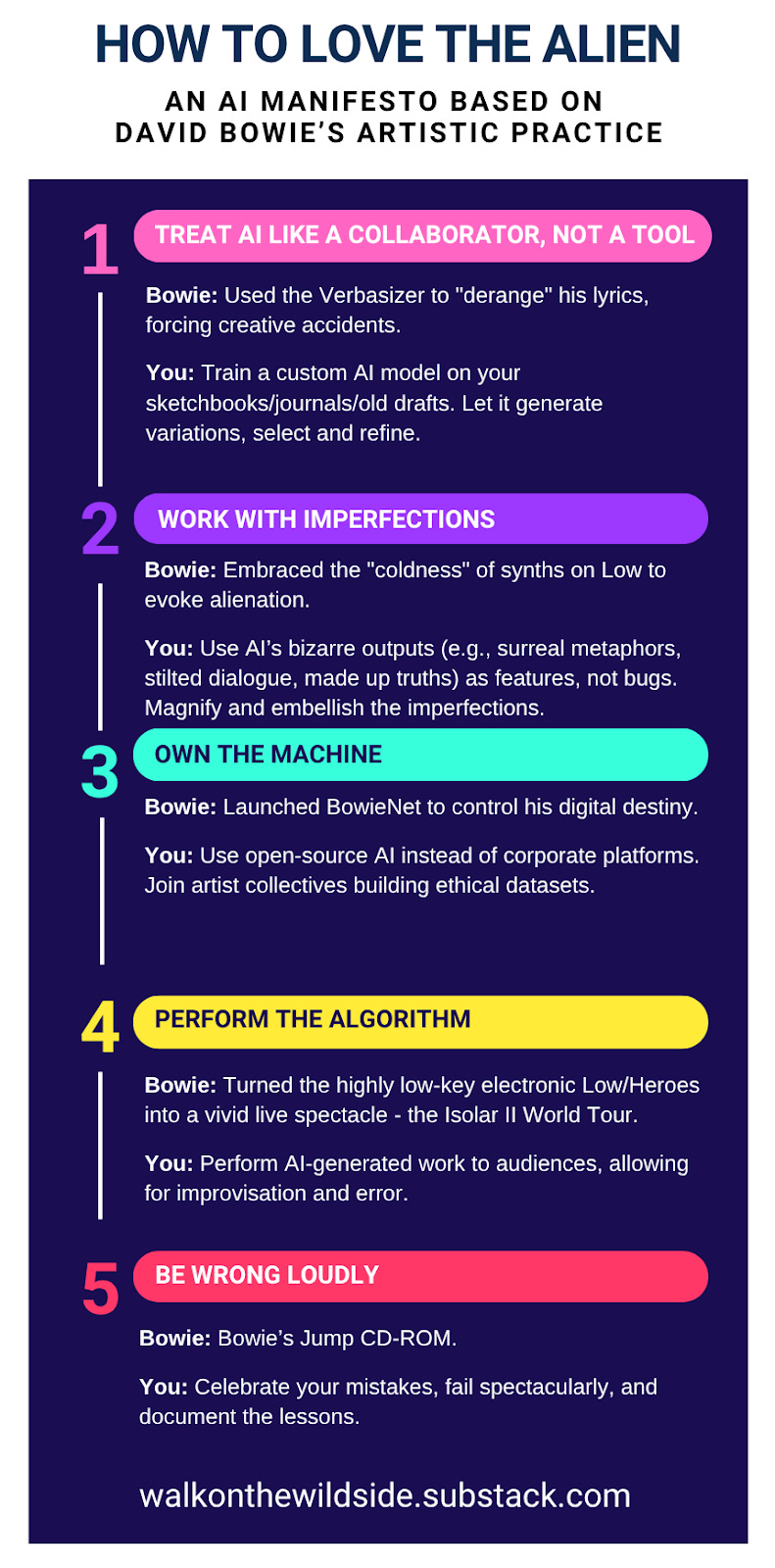

And it’s from these margins—from the outer edges of creative risk—that new models will emerge. The next wave of Bowie-type figures will likely exploit AI’s quirks, turn its glitches into style, and build ethical, open-source alternatives. They’ll hack the machine—and then remix it. So how might we hack the machine? Here’s Bowie’s playbook, adapted for the AI age.

As for the rest of us, what will we do? Will we opt out? Submit quietly? Push for reform? Or build something entirely new? Most of us, probably, will be a blend of all those things.

Because the fight isn’t against the machine. It’s for the right to name the machine. To break it open. To make it reflect our values.

Changes

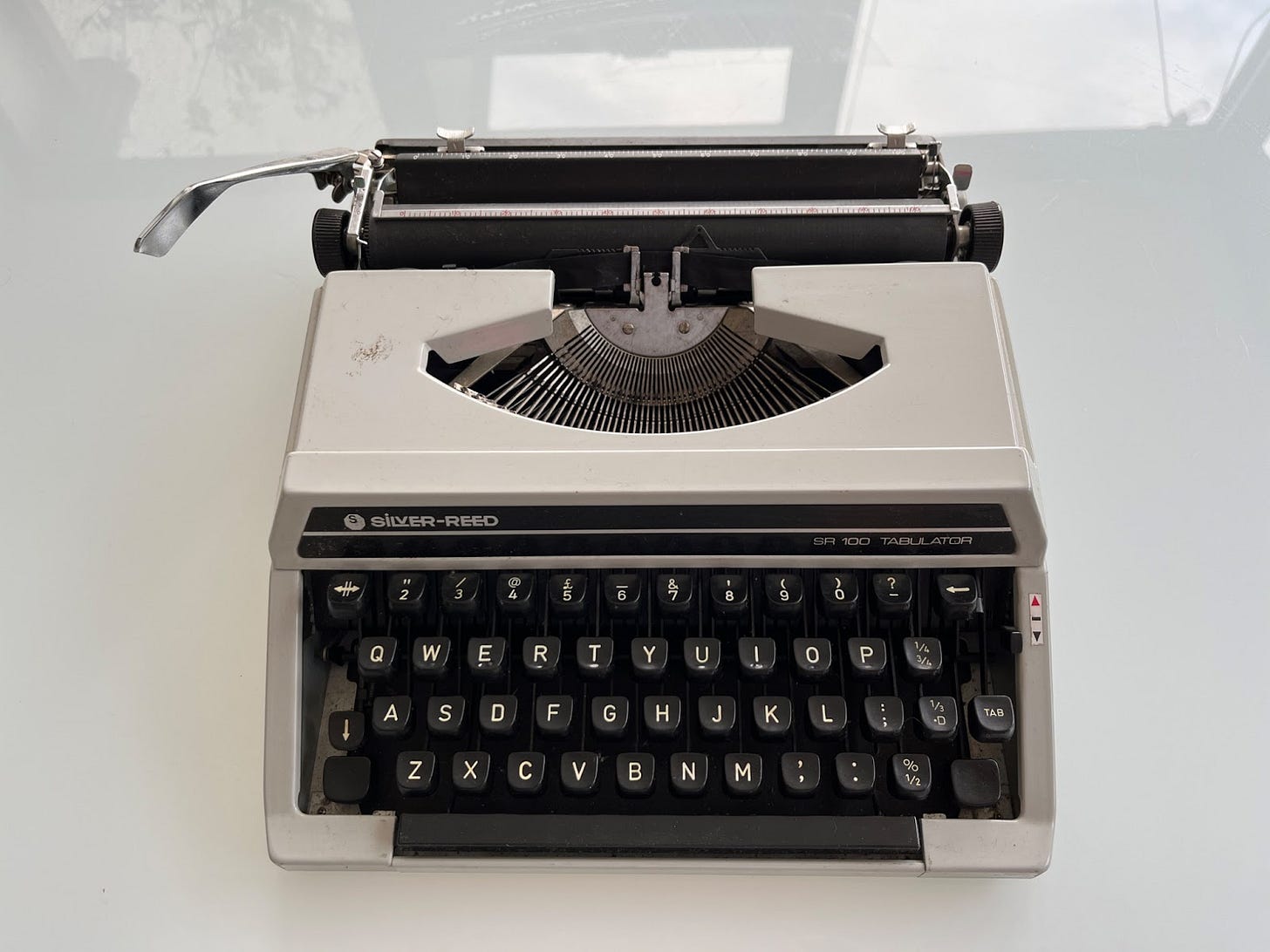

Technology changes how we think and work. The challenge is that we have no idea what those changes will be and what they will enable us to create. Here’s something else I found in my attic (yes, there was a fair bit up there). I developed my craft as a writer using this Silver Reed SR 100 typewriter, which I unearthed along with the Bowie Net CD.

Using a typewriter forced a more deliberate approach to writing. Revising the text and correcting mistakes demanded painting Snopake on the page or starting all over again. You edited in your head before pressing a key. In 1985 I bought an Amstrad PCW 8512 word processor. This totally changed how I wrote. The machine allowed for fluid, iterative writing, with effortless deletions, rearrangements and revisions, fostering a more exploratory and dynamic process. My writing process shifted from one that demanded precision, to one that encouraged experimentation.

In the late 1980s I plugged a modem into my Amstrad, and wrote a book with two other people. The internet revolutionised writing by making it faster, more collaborative, and less formal, enabling instant editing, global sharing, and real-time feedback. Over the next decade - as I moved on to a Mac - gophers, browsers and search engines totally transformed how I researched for my writing.

From the mid 2000’s I started blogging, connecting directly with readers and other writers, which changed my style of writing considerably. Now Substack builds on this, and AI is already changing my writing practice.

You can’t hide from technology, you can’t insulate yourself from it. Drawing the line at electricity is not an option. Writing by candlelight is tiring on the eyes. You can choose not to use digital tools, but you need to accept that creative practice is a rich and varied ecosystem that benefits from diverse approaches to the use of technology.

The future belongs to those who embrace their creative practice to make meaning through experiment and exploration. The future belongs to cooks, architects, storytellers and provocateurs.

Buy us a coffee

Jackie Hopfinger and I love sharing our writing and research freely — and we want to keep it that way. Our hope is that these posts spark your interest and give you a good read.

If you’ve enjoyed what we do and would like to support the time, thought, and research that goes into it, we’ve added a Buy Us a Coffee button. We really appreciate your support.

Have you heard Momus’s AI album, Ballyhoo? He is very much one of Bowie’s Kooks.

He talks a bit here: https://www.leafbox.com/interview-momus-ballyhoo/amp/

Listen here: https://momus3.bandcamp.com/album/ballyhoo

This is thought provoking Mike. You make many good points.