London, 16th August 1960

The green Morris van turned onto Old Compton Street. It was mid-afternoon, and the narrow street buzzed with life. Traffic was slow, the van weaving past taxis and delivery trucks. Inside, the young men pressed their faces against the windows, taking in the scene with a mixture of awe and apprehension. For boys who had spent most of their lives in Liverpool, Soho felt like another planet.

Beneath painted signs, weathered brick, and brightly coloured awnings, people darted in and out of cafés, delicatessens, and shops—many bearing names that hinted at their continental origins or the activities within. King Bomba, read one sign on the left, its window filled with wine bottles and strange-looking bread, while across the road, Venus Room Striptease drew middle-aged men in long raincoats. Smartly dressed men in suits and women in pencil skirts strode with purpose, mingling with a few teenagers—though it was still early for them. The van edged past a delivery truck parked awkwardly as crates of supplies were unloaded for a restaurant. A few passersby gave it curious glances—not just because it was packed with passengers, but because of the unfeasibly large load strapped to the roof rack: suitcases, drums and amplifiers all wrapped under a weathered tarpaulin.

Allan Williams leaned forward, squinting through the windscreen as he steered through the bustling street. “It’s here somewhere,” he muttered, scanning the shopfronts. Beside him, his wife, Beryl, sat with her arms crossed, wondering what exactly she had got herself into.

“Up there on the right,” came a voice from over Beryl’s shoulder. Harold Philips—known to most as Lord Woodbine—had shared the driving with Allan and knew this part of London well. After arriving from Trinidad on Windrush, he had lived here for a few years before moving to Liverpool. He had been the one to champion the boys in their earliest days, to the point that they were once known as Woodbine’s Boys. A calypsonian himself, he had even performed with them on occasion.

The van pulled across the road and parked up in front of a coffee bar with a sign that read The Act One Scene One.

“Right, boys, this is the place,” Williams said, pulling up the handbrake and glancing back at the Beatles with a grin. “Go on, stretch your legs. We’ll grab Herr Steiner, and then it’s straight to Harwich.”

They stumbled out, grateful to escape the cramped vehicle. John Lennon lit a cigarette and leaned in a doorway, trying to absorb every detail of this strange, electrifying part of London. As Allan, Lord Woodbine, Beryl, and her brother Barry disappeared into Act One Scene One, George Harrison—the youngest of the group—and Pete Best, who had only been invited to join the band four days earlier, wandered along the road to inspect the window of a sex shop. Such places were rare in Liverpool.

Paul McCartney and Stuart Sutcliffe lingered near the café directly opposite, peering into its window, their grins betraying a mix of excitement and nerves. This was the famous 2i’s Coffee Bar, where many of Britain’s biggest rock and roll stars had been discovered on its tiny basement stage. That very week, Cliff Richard, The Shadows, and Johnny Kidd & The Pirates occupied the top three spots in the charts—all of them launched from the 2i’s. Back home, their Casbah Coffee Club had been modeled after this place, but it looked nothing like the real thing. Through the window, a gleaming stainless steel espresso machine belched steam, while a towering Ami 200 jukebox blasted music. And, of course, the 2i’s was the reason they were here.

Allan Williams, a former singer, ran his own coffee bar in Liverpool—the Jacaranda. Popular with art students and the West Indian community, it owed some of its eclectic atmosphere to Lord Woodbine’s Royal Caribbean Steel Band. His wife Beryl, born to Chinese immigrants, added to the mix, though her background also made the two of them the target of abuse from some locals. Williams managed several groups in Liverpool—a city with a growing reputation for producing high-quality music acts.

In May 1960, Bruno Koschmider had asked him to provide a band for a residency at his Indra Club in Hamburg. Williams had driven down to the 2i’s with Liverpool’s top group—Derry & The Seniors—for an audition. Koschmider was impressed and booked them on the spot. Over coffee next door at Heaven and Hell, the two men struck a deal: any band Williams deemed good enough for the Indra, Koschmider would take without question.

Three months later, Koschmider called again, asking for another group. Unfortunately, Liverpool’s next-best act—Rory Storm and the Hurricanes (with Ringo Starr on drums)—was locked into a summer residency at a North Wales holiday camp. So Williams hastily arranged passports for the untested, often unreliable, and generally unprofessional Beatles. But passports were the least of their problems—when the call came, they didn’t even have a drummer. That was how Pete Best ended up in the band.

Now, on their way to Hamburg, they had stopped in Soho to collect their tenth passenger—Herr Steiner, an Austrian working at Act One Scene One, who was to serve as Koschmider’s interpreter.

Before long, the boys were clambering back into the van, squeezing together as Steiner took a seat up front. The air inside was thick with cigarette smoke and the faint remnants of their packed lunches. The engine chuntered into life, and they pulled away from Old Compton Street.

They left Soho as unproven teenagers. In the coming weeks and months, they would be commanded to “Mach schau! Mach schau!” and learn their craft, playing five- or six-hour sets over 48 consecutive nights. Eighteen hours after leaving London, a wrong turn by Williams landed them in Arnhem, where they were photographed at the war memorial.

A creative home

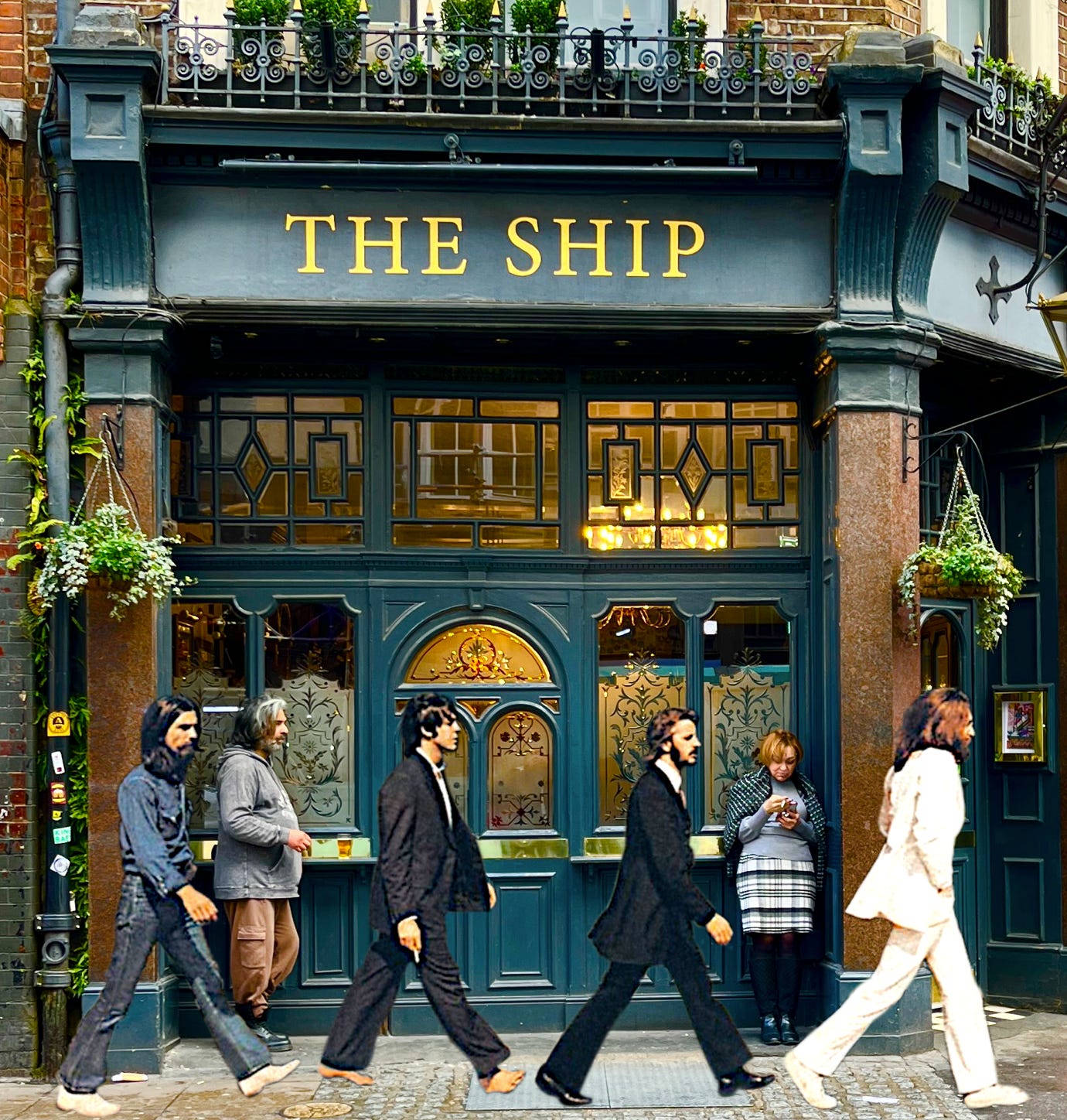

They may have come from Liverpool and honed their craft in Hamburg, but The Beatles were, in many ways, a Soho band. This vibrant and eclectic square mile of London played a pivotal role in shaping their career, and together, they became symbols of a post-war, post-colonial Britain reinventing itself for a new era. In the 1960s, Soho was a hotbed of creativity and cultural innovation, teeming with music venues, recording studios and an entrepreneurial spirit that made it the perfect incubator for aspiring musicians. But it was more than that: Soho was a microcosm of a changing Britain—open, tolerant, and culturally diverse, reflecting the shifting identity of a nation emerging from the shadows of empire and war. Within this unique cultural ecosystem, The Beatles' talent found fertile ground to take root and flourish, embodying and indeed accelerating the optimism and renewal of the 1960s.

It was in Soho that The Beatles secured the two pivotal breaks that launched their professional career. The neighbourhood offered not just a place to socialise with fellow musicians, but also the resources they needed to thrive. Whether it was buying a guitar, a drum kit, or the latest fashion, Soho had it all. Music publishers, recording studios, and influential publications like NME and Melody Maker were all part of Soho's tightly knit creative economy. The Beatles, with their eclectic influences and boundary-pushing sound, mirrored Soho's own melting pot of cultures and ideas. Together, they represented a break from the past and a bold step toward a more inclusive and dynamic future.

Even their final live performance, played from the rooftop of Apple Corps just beyond Soho's western boundary, echoed across the neighbourhood's rooftops, marking a fitting end to their journey in the place that had helped shape their beginnings. In this moment, as in so many others, The Beatles and Soho intersected to capture the spirit of a nation in transition—a Britain shedding its post-war austerity and colonial legacy, and embracing a new identity defined by creativity, diversity, and hope.

A musical journey

In this series of posts we will take you on a musical journey through Soho with The Beatles. We will detail the key locations that tell the story of The Beatles in Soho, presented chronologically. The final part will include a map and a playlist.

We are planning to organise a guided walking tour of The Beatles in Soho in the future, along with our other musical Soho walks. Let us know if you are interested!

Buy us a coffee

We love sharing our writing and research freely — and we want to keep it that way. Our hope is that these posts spark your interest and give you a good read.

If you’ve enjoyed what we do and would like to support the time, thought, and research that goes into it, we’ve added a Buy Me a Coffee button. The idea is that it will go towards the costs of our research and running the guided walks, which we do as charity fundraisers. We’re committed to keeping this space, and our activities, open and accessible.

Lovely stuff, and I admire your chutzpah in trying to claim the Fabs as London’s finest…ha-ha!

But I do get your point about Soho as the great incubator of many of Britain’s cultural progeny. And, of course, it was also pivotal to the Sex Pistols, which is why I was always attracted to the ‘idea’ of it as a kid in Manchester. It’s the part of London I always loved most when living there, and miss most of all today now I’m many miles away.

Looking forward to the rest of the Merseybeat-on-the-Thames tour!

So interesting, thanks Mike yet again for bringing us history and stories.